The wrists and hands are body parts we use repeatedly throughout the day, but sadly, we generally take them for granted.

However, things change when someone begins to have pain – and having pain in the wrist or hands is quite common. In a recent study, physical therapists reported that the wrist and hand, as well as the upper back area, had the second highest injury prevalence (23 percent of their patients). This was second only to the low back as the most frequent area injured.1

As chiropractors, we use our wrists and hands with every patient in every aspect of patient care. In daily practice, especially if you treat extremities regularly, wrist and hand pain is quite common. It can range from simple soreness to full-blown radiating pain. In an effort to understand how patients develop pain or biomechanical issues from these areas, let's take a moment to review the clinical anatomy.

Image 1: The bones of the hand.

Wrist / Hand Anatomy

Image 1: The bones of the hand.

Wrist / Hand Anatomy

The wrist is said to be the most complex joint in the body. It is formed by eight carpal bones grouped in two rows with somewhat restricted motion between them. From radial to ulnar, the proximal row consists of the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum and pisiform bones. In the same direction, the distal row consists of the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate and hamate bones. There is also involvement of the proximal portions of the five metacarpal bones of the hand. (Image 1)

All carpal bones participate in wrist function except for the pisiform, which is a sesamoid bone through which the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon passes. The scaphoid serves as a bridge between the two rows; therefore, it is often susceptible to fracture or injury. The distal row of carpal bones is strongly attached to the proximal regions of the second and third metacarpals, forming a fixed unit. All other structures (mobile units) move in relation to this stable unit. The flexor retinaculum, which attaches to the pisiform and hook of hamate on the ulnar side, and to the scaphoid and trapezium on the radial side, forms the roof of the carpal tunnel. (Image 2)

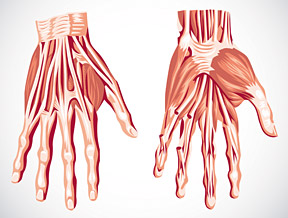

Image 2: The hand showing muscles and tendons.

Common Conditions

Image 2: The hand showing muscles and tendons.

Common Conditions

As we know, biomechanical movement and stability of the wrists and hands are critical to normal functioning. If everything is working right, the patient is none the wiser. In practice, we see a variety of wrist ailments. Many of these ailments can be traced back to specific traumas or incidents. However, it is quite common to hear the patient relate more of an insidious onset. Common conditions patients may present with include the following:

Thumb sprain: Breaking a fall with the palm of the hand or taking a spill on the slopes with a hand strapped to a ski pole could leave your patient with a painful thumb injury. The ulnar collateral ligament may be sprained. This ligament acts like a hinge and helps the thumb to function properly.

Wrist sprain: When falling forward, especially when running or rollerblading, the natural response is to put the hands out in front to catch oneself. Unfortunately, this natural response causes a person to land on their palms, bending the wrist backward and possibly stretching or tearing the ligaments connecting the bones in the wrist.

Hand fractures: Fractures of the metacarpals (the bones in the hand just before the knuckles) and the phalanges (the bones between the joints of the fingers) are also common sports injuries. Metacarpal fractures account for 30-40 percent of all hand fractures.2 The most common fracture of the metacarpals is a boxer's fracture; it usually occurs when a person strikes an object with a closed fist. With a boxer's fracture, the fifth metacarpal joint is depressed and the surrounding tissue is tender and swollen.

Wrist fracture: Wrist fractures are common both in sports and motor-vehicle accidents. The break usually occurs during a fall on the outstretched wrist. The angle at which the wrist hits the ground may determine the type of injury. The more the wrist is in extension, the more likely the scaphoid bone will break. With less wrist extension, it is more likely that the radius will break.

Distal radius fractures (Colles' fractures) are very common, and the break usually happens when a fall causes someone to land on his/her outstretched hands with the wrists in slight extension.

Scaphoid fractures occur in the carpal bones, but they are not always immediately obvious. Many people with a fractured scaphoid think they have a sprained wrist instead of a broken bone, because there is no obvious deformity and very little swelling.

DeQuervain's syndrome: This is a prevalent injury in racquet sports and in athletes who use a lot of wrist motion, especially repetitive rotating and gripping. Overuse of the hand may eventually cause irritation of the tendons along the thumb side of the wrist. This irritation causes the lining around the tendon to swell, making it difficult for the tendons to move properly.

Carpal tunnel syndrome: The carpal tunnel is a narrow, tunnel-like structure in the wrist. The floor and sides of this tunnel are formed by wrist (carpal) bones. The top of the tunnel is covered by the transverse carpal ligament.

The median nerve travels from the forearm into the hand through this tunnel in the wrist. It controls feeling in the palm side of the thumb, index finger, and long fingers. The nerve also controls the muscles around the base of the thumb. The flexor tendons that bend the fingers and thumb also travel through the carpal tunnel.

When the tissues surrounding the flexor tendons in the wrist swell and put pressure on the median nerve, they create symptoms like numbness, tingling, and pain in the lateral 3.5 digits. Symptoms of CTS include pain, numbness, and tingling in the hands. Based on a recent study, one in five symptomatic subjects would be expected to have CTS based on clinical examination and electrophysiologic testing.3

Ulnar tunnel syndrome: This syndrome causes numbness and tingling in the little finger and along the outside of the ring finger. There is entrapment or irritation of the ulnar nerve as it passes through the tunnel on the medial side of the wrist. The pisiform or hook of hamate bones can impinge the nerve, creating motor and sensory deficits.

Image 3: Lateral wrist adjustment.

Evaluation / Treatment Strategies

Image 3: Lateral wrist adjustment.

Evaluation / Treatment Strategies

As we have seen in other parts of the body, there is a unifying theme to many of the disorders of the wrist. Aside from the obvious signs of pain, swelling or inflammation, there exists biomechanical dysfunction of the bones. As chiropractors, we know that by adjusting the bones of the wrist and hand, we restore joint motion and improvements can occur.

Adjustments of the carpal bones are not terribly difficult. Usually, we take information from the patient's history (i.e., mechanism of injury) along with orthopedic testing and motion / static palpation. Much can be felt with your palpation, as the bones are small enough that they can be "sheared" nicely. Motion / static palpation of the wrist and hand can be done in three phases:

- With one hand, grasp the distal radius / ulna and with the other hand, grasp the proximal row of carpal bones.

- With one hand, grasp the proximal row of carpal bones and with the other hand, grasp the distal row of carpal bones.

- With one hand, grasp the distal row of carpal bones and with the other hand, grasp the proximal metacarpals.

Image 4: Posterior wrist adjustment.

Due to general use of the wrist and everyday wear and tear, I often find three major patterns of wrist bone misalignment. These bones can be adjusted by contacting your thumbs and stabilizing with your other fingers. (See images depicting each adjustment.)

Image 4: Posterior wrist adjustment.

Due to general use of the wrist and everyday wear and tear, I often find three major patterns of wrist bone misalignment. These bones can be adjusted by contacting your thumbs and stabilizing with your other fingers. (See images depicting each adjustment.)

The scaphoid, trapezium tend to move in a lateral (radial) direction. Adjusting these bones utilizes a distraction maneuver with a lateral-to-medial prestress. With the prestress, a long-axis thrust or pull will move the bones back, often with an accompanying audible. (Image 3)

The triquetral moves medial ("ulnarward"). Adjusting this bone utilizes a distraction maneuver with a medial-to-lateral prestress. With the prestress, a long-axis thrust or pull will move the bones back with an audible. (Image 4)

Image 5: Anterior wrist adjustment.

The lunate, trapezoid, capitate and hamate drop inferior. Adjusting these bones involves prestressing from inferior to superior, in essence creating more room for the carpal tunnel below. (Image 5)

Image 5: Anterior wrist adjustment.

The lunate, trapezoid, capitate and hamate drop inferior. Adjusting these bones involves prestressing from inferior to superior, in essence creating more room for the carpal tunnel below. (Image 5)

Compression of the metacarpal / phalangeal joints is common due to ADLs or arthritis. Gentle distraction of all parts of the phalanges will gap the joints and provide relief and increased motion. (Image 6)

Remember, manual adjusting is never the only option. Spring-loaded instruments, a drop table or a portable speeder board also work in getting movement to the bones. Also, the patterns described above are never set in stone. Use your palpation skills and find out how the bones have moved out of position; then put them back.

Protect Your Wrists / Hands

Image 6: Phalanges adjustment.

I want to end by reminding you about how strenuous and stressful our job is to the joints of our hands and wrists. Take heed of some ergonomic considerations to keep your hands and wrists in good shape for years to come. Avoid adjusting maneuvers that put your wrist in extreme extension. We are usually talking about side-posture adjustments, but it can be any of your manual adjustments. Watch your table height and have that patient roll toward you or into whatever position will help your body. Keep that wrist as straight as possible so you don't jam your carpal bones.

Image 6: Phalanges adjustment.

I want to end by reminding you about how strenuous and stressful our job is to the joints of our hands and wrists. Take heed of some ergonomic considerations to keep your hands and wrists in good shape for years to come. Avoid adjusting maneuvers that put your wrist in extreme extension. We are usually talking about side-posture adjustments, but it can be any of your manual adjustments. Watch your table height and have that patient roll toward you or into whatever position will help your body. Keep that wrist as straight as possible so you don't jam your carpal bones.

Chronically tight muscles in your forearms and hands can create stress on the bones and joints. Get regular muscle work or put your physiotherapy modalities / machines on your body to keep your soft tissues pliable and relaxed.

Get adjusted yourself! You have to find someone who knows how to adjust extremities so that they can work on your hands / wrists also. Our patients have shown us that when we wait and hope a problem will go away, it almost always gets worse. If you have hand / wrist / elbow pain, tightness or tendonitis, get it looked at before you have too much pain and you can't adjust your patients.

The wrists and hands do command our attention because they do so much work for us and our patients. With a little practice, it is amazing how effective we can be at helping with pain in these regions.

References

- Holder N, Clark H, DiBlasio J, Hughes C, Scherpf J, Harding J Shepard K. Cause, prevalence, and response to occupational musculoskeletal injuries reported by physical therapists and physical therapist assistants. Phys Ther, July 1999;79(7):642-652.

- Ashkenaze DM, Ruby LK. Metacarpal fractures and dislocations. Orthop Clin North Am, 1992;23:19.

- Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, Ornstein E, Ranstam J, Rosén I. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA, 1999 Jul 14;282(2):153-8.

This is the fifth in a series of six articles dedicated to the extremities, covering clinical discussions from the feet to the ankles, knees, hips, hands / wrists and elbows to the shoulders. Part 1 appeared in the Feb. 12, 2012 issue; part 2 ran in the April 22 issue; part 3 appeared in the July 1 issue; and part 4 ran in the Aug. 12 issue.

Dr. Kevin Wong, earned a BS in exercise physiology from the University of California – Davis and his DC degree from Palmer Chiropractic College West. He practices in Orinda, Calif., and serves the Lamorinda, Berkeley, Walnut Creek and many other East San Francisco Bay Area communities. He is an expert on foot analysis, walking and standing postures, and orthotics, and lectures nationwide on spinal and extremity adjusting.