Recently, in the professional journal Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, authors Leboeuf-Yde, Innes, Young, Kawchuk and Hartvigsen1 discuss the possibility of initiating a "professional divorce" between two factions in the profession.

Later in the article, the authors draw an analogy between the two adversarial chiropractic wings and a marriage between squabbling spouses; and point out that marriage partners either resolve their differences or agree to disagree and dissolve their marriage partnership. They conclude with the following:1

"We have argued that the situation within the chiropractic profession corresponds very much to that of an unhappy couple that stays together for reasons that are unconnected with love or even mutual respect. The current marital disharmony clearly goes beyond the scope of continuing to live unhappily with 'another person' of a differing world view. The alternative to this unhappy family structure would be an amicable divorce."

The chiropractic profession has a long history of professional disharmony. The roots go back to the very beginning of the profession as divisions developed and the leaders of adversarial groups vied for control of the infant child, chiropractic.

Setting the Table for Civil War

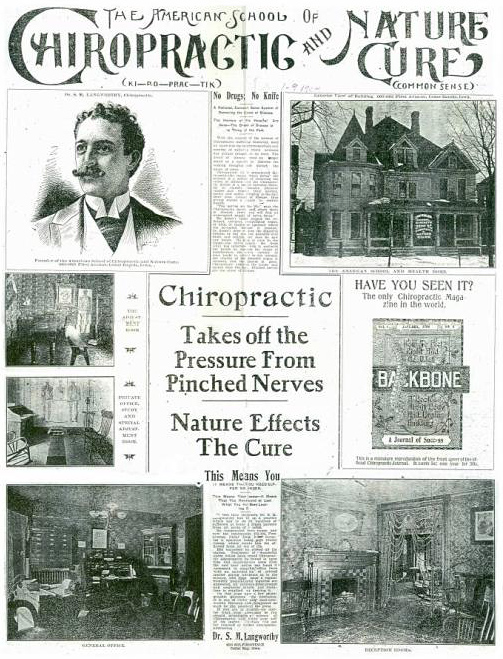

D.D. Palmer granted a diploma that stated the graduate of his school was certified to "practice and teach" chiropractic.2 Many of the early graduates did just that. During the profession's first decade, several schools were teaching chiropractic; among these were the National School of Neuropathy and Psycho-Magnetic Healing in Minneapolis, and Solon M. Langworthy's American School of Chiropractic & Nature Cure in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.3 A number of individual practitioners also established apprenticeship programs, and apprentice-trained chiropractors took on apprentices of their own.4 Gibbons5 reports that, as a result of these apprentice relationships, as many as 200 chiropractors may have populated the state of Minnesota by 1905.

Langworthy's American School of Chiropractic & Nature Cure had established the first two-year systematic chiropractic school curriculum. That course of instruction was longer and more progressive (i.e., broad scope) than that of the Davenport Palmers' school.3,5 Additionally, the apprentice-trained chiropractors of Minnesota practiced a version of the art that the Palmers did not believe represented the profession as they had envisioned it, either technically or philosophically.6

With this relatively large number of DCs practicing in the state of Minnesota, along with the backing of one of the earliest competitors of the Davenport Palmers, Minnesotan chiropractors were emboldened to attempt to get a chiropractic bill passed through the state legislature.

Daniel D. Riesland, an apprentice-trained chiropractor from Duluth, and Solon Langworthy successfully lobbied the Minnesota legislature to pass a chiropractic bill that would have established a five member board of chiropractic examiners; required that applicants have attended a school with a two-year chiropractic curriculum; and grandfathered in the appointed members of the Minnesota Board of Chiropractic Examiners, even if they had not attended the two-year school.

In early 1905, Riesland and Langworthy were successful in gaining passage of the bill in both houses of the Minnesota legislature by significant majorities. If signed by then-Governor John A. Johnson, Langworthy's progressive two-year curriculum would have been codified into state law and Palmer graduates would not have been eligible to sit for the examination.

Civil War Erupts

The Davenport Palmers understood the stakes of this political game. Old Dad Chiro cranked up his Underwood typewriter and wrote to each of the Minnesota legislators on March 7, 1905. In his letter, D.D. railed against the "mixer" nature of the bill and the fact that the proposed members of the board of examiners would be established as chiropractic "czars" of the state. He concluded that:

FIG 2 Newspaper coverage of the internal squabble. (courtesy Chiropractic History and the Association for the History of Chiropractic).

"It would be dangerous to confer upon them the undisputed, absolute, unconditional, dictatorial, despotic power that they are asking. This bill clothes the board with legalized monopoly; it is granting them a privilege, a franchise that they will not despise for enriching themselves at the expense of those of whom they have full control."6

FIG 2 Newspaper coverage of the internal squabble. (courtesy Chiropractic History and the Association for the History of Chiropractic).

"It would be dangerous to confer upon them the undisputed, absolute, unconditional, dictatorial, despotic power that they are asking. This bill clothes the board with legalized monopoly; it is granting them a privilege, a franchise that they will not despise for enriching themselves at the expense of those of whom they have full control."6

In late March 1905, D.D. met with Governor Johnson and pleaded with him not to sign the bill into law on the basis of the arguments he had raised with the Minnesota legislators. As the discoverer and developer of the new science, D.D. proclaimed that he, and only he, was qualified to decide what should or should not be contained in any legislation governing his profession.

How much influence D.D.'s pleadings had over the governor's decision not to sign the bill is unknown. The medical lobby that had been caught asleep at the wheel by the passage of the bill through the Minnesota house and senate sprang into action and lobbied hard against the governor's signature.

Witnessing the broken ranks among the chiropractors likely resulted in great celebration among the medical lobby. Divide and conquer is an often-used strategy to defeat one's enemies, and the Palmer and Langworthy camps played right into that trap. The desire for power, influence, legacy and money was the bait.

FIG 3 Governor John A. Johnson circa 1905 (courtesy Chiropractic History and the Association for the History of Chiropractic).

In his remarks in defense of vetoing the bill, Governor Johnson stated that chiropractic was a discovery of recent origin, unproven and promoted and promulgated by uneducated men with little knowledge of the sciences of "anatomy and kindred subjects."6 It would be nearly a decade before the enactment of the first law licensing chiropractic as a legal profession.

FIG 3 Governor John A. Johnson circa 1905 (courtesy Chiropractic History and the Association for the History of Chiropractic).

In his remarks in defense of vetoing the bill, Governor Johnson stated that chiropractic was a discovery of recent origin, unproven and promoted and promulgated by uneducated men with little knowledge of the sciences of "anatomy and kindred subjects."6 It would be nearly a decade before the enactment of the first law licensing chiropractic as a legal profession.

Doomed to Repeat the Past?

The tradition of disharmony within the ranks of the chiropractic profession has a long history that extends back almost to the very beginning of the profession. I am sure chiropractic's adversaries delight in the fact that, when faced with difficult choices regarding the advancement of the profession, the opposing political factions within the profession "circle the wagons" and shoot inward.

Whether the strained marriage of so-called "traditional" and "evidence friendly" chiropractors will succeed is a question yet to be resolved. What is the proper solution to this problem? That is a topic beyond the scope of this article and is far above the pay grade of this author. I can state, however, that as the Spanish philosopher George Santayana said, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." Our political adversaries are happy that chiropractors cannot remember their past.

References

- Leboeuf-Yde C, Innes SI, Young KJ, et al. "Chiropractic, One Big Unhappy Family: Better Together or Apart?" Chiro & Manual Ther, 2019;27(4):8 pages.

- Weise G, Petersen D. Chiropractic Schools and Colleges. In: Petersen D, Weise G (editors). Chiropractic: An Illustrated History. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Yearbook, Inc., 1995:338-387.

- Troyanovich SJ, Gibbons RW. "Finding Langworthy: The Last Years of a Chiropractic Pioneer." Chiro History, 2003;23(1):9-17.

- Haldeman S. "Almeda Haldeman, Canada's First Chiropractor: Pioneering the Prairie Provinces, 1907-1917." Chiro History, 1983;64-67.

- Troyanovich SJ, Coleman RR. "Origins of the Use of Mechanical Traction for Reduction of the Chiropractic Subluxation." Chiro History, 2004;24(2):1-10.

- Gibbons RW. "Minnesota, 1905: Who Killed the First Chiropractic Legislation?" Chiro History, 1993;13(1):26-32.

Dr. Steve Troyanovich is the secretary of the Association for the History of Chiropractic. Contact him with questions and comments at

. The AHC has preserved the credible history of the profession as its sole mission through the publication of the scholarly journal, Chiropractic History. Stories such as this one may be accessed through the pages of the AHC's journal (www.historyofchiropractic.org).