In any given year, nearly one in 100,000 adults will develop a vertebral artery dissection (VAD).1 Factors that increase the risk of dissection include elevated homocysteine levels, Marfan syndrome, family history of stroke, migraines, and even seasonal allergies (vertebral artery dissections are more likely to occur in the fall).2-3

Progression / Common Symptoms

If the initial damage to the lining of the vertebral artery is minor and is left alone, the artery often heals without incident as platelets become adherent to the site of the tear, mix with fibrin and form a "white thrombus" that retracts into the vessel wall.4 With these minor injuries, blood continues to make its way to the brainstem, and frequently the only sign the artery is damaged is referred pain from inner lining of the artery to the head and/or neck.

To prove that minor damage to the vertebral artery is capable of referring pain, researchers inflated balloons that had been inserted into the vertebral arteries of healthy subjects and noted the stretch induced by the inflating balloons referred pain from the subjects' foreheads and cheeks to their occiputs, posterior necks and even upper trapezius muscles.5

If the inner lining fails to heal, blood, being forced under systolic pressure, may enter the artery wall through the initial tear, thereby splitting different layers of the artery and forming a subintimal hematoma or a subadventitial aneurysm. Either way, blood flow through the affected vertebral artery becomes significantly diminished and symptoms related to brainstem infarct often develop. VADs are serious injuries with a 2 percent mortality rate during the first month and 1 percent mortality rate per year for the next 10 years.6

If the inner lining fails to heal, blood, being forced under systolic pressure, may enter the artery wall through the initial tear, thereby splitting different layers of the artery and forming a subintimal hematoma or a subadventitial aneurysm. Either way, blood flow through the affected vertebral artery becomes significantly diminished and symptoms related to brainstem infarct often develop. VADs are serious injuries with a 2 percent mortality rate during the first month and 1 percent mortality rate per year for the next 10 years.6

Besides the telltale intense headache so often associated with VAD, a range of ocular disturbances may occur; e.g. diplopia, blurred vision, conjugate gaze paralysis, and/or nystagmus. Additional symptoms associated with vertebral artery dissection are vertigo, slurred speech, difficulty swallowing, nausea/vomiting, and facial and/or extremity paresthesias.

Taking the Blame Off Chiropractic

While neurologists are quick to blame the chiropractic profession any time someone suffers a VAD, this is in large part due to the fact that early research showed a disproportionate number of patients suffering vertebral artery dissection had cervical manipulation within a few days prior to developing their stroke. The temporal connection between chiropractic adjustments and VAD initially seemed to clearly suggest cervical adjustments, and/or any other vigorous movement of the neck, could damage a vertebral artery, causing a healthy vertebral artery to dissect.

More recently, researchers are discovering that chiropractic manipulation is not a risk factor for developing vertebral artery dissection.7 To prove that chiropractic care does not result in an increased risk of VAD, Cassidy, et al.,7 evaluated the health records of more than 12 million Canadians followed for nine years.

Over that time, there were 818 cases of vertebral/basilar artery dissection which occurred during 109,020,875 person-years of observation (i.e., 12 million people followed for nine years). The data was then analyzed to see if there was a higher prevalence of VAD in patients who received chiropractic care compared to conventional medical care (which would have confirmed that chiropractic care was potentially dangerous to the vertebral artery).

The final analysis of their data confirmed that although patients with vertebral artery dissections were more likely to seek chiropractic and/or medical care, there was essentially no difference in the development of a vertebral artery dissection whether the patient saw a chiropractor and/or a medical doctor. The results of this study suggest a damaged vertebral artery produces symptoms that cause the patient to seek medical attention, and that chiropractic care is no more dangerous to the vertebral artery than conventional medical intervention.

The authors' 2017 follow-up paper on carotid artery dissections also confirmed chiropractic care is no more likely to result in carotid artery dissection than medical intervention.8

Manipulation or Not?

It must be emphasized that the research by Cassidy, et al.,7-8 in no way suggests a traumatized vertebral artery can tolerate the mechanical stress associated with even gentle manipulation, especially rotational and/or extension manipulation.2 In their conclusion, Cassidy, et al.,7 state it is "possible that chiropractic manipulation, or even simple range-of-motion examination by any practitioner, could result in a thromboembolic event in a patient with a pre-existing vertebral artery dissection."

The fact that so many people suffer vertebral artery dissection within minutes following excessive neck motions associated with practicing yoga, stargazing, ceiling painting, and even having their hair washed in a beauty salon, confirms that while a healthy vertebral artery is most likely not stressed with even rapid, full-range neck motions, a dissected vertebral artery is most likely structurally weaker and should therefore not be mechanically stressed with upper cervical chiropractic manipulation.9 This is especially true for upper cervical adjustments incorporating rotation and/or extension.

Nearly 20 years ago, I made a case for practitioners to abandon all rotation and/or extension upper cervical manipulations in favor of adjustments incorporating lateral flexion of the upper cervical spine.2 In my experience, upper cervical manipulation incorporating lateral flexion produces the same positive outcomes with a reduced risk of iatrogenic injury.

The connection between upper cervical rotation and VAD is supported by the recent finding that 80 percent of right-handed golfers who suffer VAD do so between the atlas and axis on their right side.10 If cervical rotation does not stress the vertebral artery, there would not be a clear side-dominance for VAD with upper cervical rotation.

Identifying At-Risk Patients

Because chiropractic manipulation is significantly safer than the vast majority of medical interventions for managing neck pain (e.g., 1 in 1,200 people who take NSAIDs daily for two months will die from gastroduodenal complications),11 the challenge for our profession is how to identify people with active dissections so they are not manipulated. Since pre-manipulative VAD screening tests such as Maigne's, George's, and Wallenberg's tests have been proven to be useless for identifying at-risk patients prone to vertebral artery dissection, the most important factor in identifying a patient with an active dissection is to pay close attention to their symptoms.

According to Terrett,9 the most common symptoms associated with VAD are vertigo and/or headache. While vertigo by itself is generally not indicative of vertebral artery dissection, almost every patient with a VAD reports the associated headache / neck pain is "unlike any pain I have ever experienced before." This statement is a harbinger of a poor outcome with manipulation, as it is a strong indication of a possible VAD.

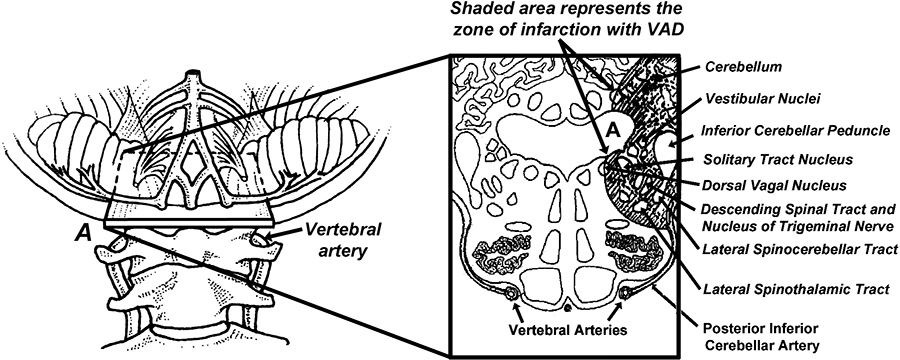

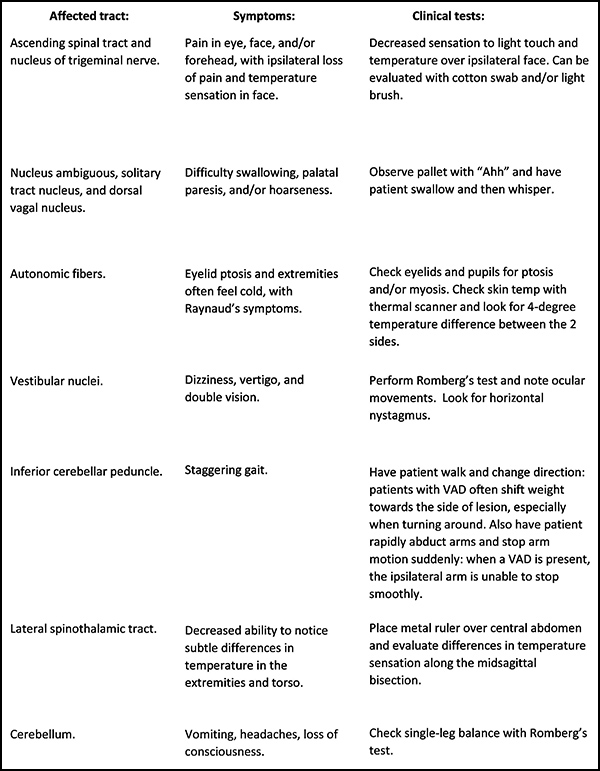

In addition to evaluating subjective complaints, it is imperative that every chiropractor perform a thorough neurological examination of the areas of the brainstem most likely to be affected by VAD (Fig. 1).

With practice, the full neurological work-up can be performed in minutes. Although vertebral artery dissections are rare, the often-catastrophic consequences associated with this difficult-to-diagnose condition make thorough evaluation and examination essential.

References

- Lee VH, Brown RD Jr, Mandrekar JN, et al. Incidence and outcome of cervical artery dissection: a population-based study. Neurology, 2006;67:1809-12.

- Michaud T. Uneventful upper cervical manipulation in the presence of a damaged vertebral artery. J Manip Phys Ther, 2002;25:472-483.

- Schievink WI, Wijdicks EM, Kuiper JD. Seasonal pattern of spontaneous cervical artery dissection. J Neurosurg, 1998;89:101-3.

- Fields WS. Role of Platelets in Arterial Thrombosis. In: Netter FH, editor. The Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations, Volume 1. Princeton, NJ: Ciba Pharmaceutical Company, 1986: p. 52.

- Nicholls FT, Mawad M, Mohr JP, et al. Focal headache during balloon inflation in the vertebral and basilar arteries. Headache, 1993;33:87-89.

- Bassetti C, Carruzzo A, Sturzenegger M, Tuncdogan E. Recurrence of cervical artery dissection. A prospective study of 81 patients. Stroke, 1996;27(10):1804-7.

- Cassidy JD, Boyle E, Côté P, et al. Risk of vertebrobasilar stroke and chiropractic care; results of a population-based case-control and case-crossover study. Spine, 2009;33:2838-.

- Cassidy JD, Boyle E, Côté P, et al. Risk of carotid stroke after chiropractic care: a population-based case-crossover study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 2016 Nov 21 (epub ahead of print).

- Terrett AGJ. Current Concepts in Vertebrobasilar Complications Following Spinal Manipulation. West Des Moines, IA: NCMIC Group, Inc., 2001.

- Choi M, Hong J, Lee J, et al. Preferential location for arterial dissection presenting as golf-related stroke. Am J Neuroradiology, November 2014;35:1-4.

- Tramer MR, Moore RA, Reynolds DJM, McQuay HJ. Quantitative estimation of rare adverse events which follow a biological progression: a new model applied to chronic NSAID use. Pain, 2000;85:169-82.

Click here for more information about Thomas Michaud, DC.