Editor's Note: The first article in this series (January 2019) introduced the back squat assessment including proper performance.

The squat has been recognized as both a functional movement assessment and a foundational exercise for activities of daily living, rehabilitation and sports performance.

Suboptimal or faulty movement patterns will, over time, exacerbate arthrokinematic degeneration, decrease performance and increase the risk for injury.

Kushner and Meyer's team have proposed using the BSA as an assessment and training tool with 30 observable functional checkpoints. This article addresses evaluating the upper-body domain (head, neck and torso) for movement, strength / stability and mobility, accounting for nine of their proposed 30 technical criteria.

During the BSA, all spinal curves and anatomical checkpoints need to be maintained. Loss of spinal curves and alignment is often related to a combination of poor psychomotor skills, lack of strength / stability and segmental lack of joint motion. Therefore, your toolbox needs to include soft-tissue techniques, corrective exercises and CMT to completely address any deficits.

Teaching Proper Squat Mechanics

While muscular and joint imbalances can significantly affect squat mechanics, the first corrective action is verbal cueing and age-appropriate instructions to ensure the deficit is not simply a lack of knowledge of the expected goal or poor muscular coordination. Common verbal instructions for the patient's relative body positions can include:

- Head: "Hold your head flat"

- Thoracic: "Widen your chest"

- Trunk: "Point belly button forward"

- Hips: "Square your hips"

- Knee, frontal plane: "Point kneecaps straight ahead"

- Tibial progression angle: "Straighten your shins"

- Feet: "Grip the floor with your heels"

- Descent: "Reach back for a chair"

- Depth: "Keep hips at least knee high"

- Ascent: "Lead with your chest"

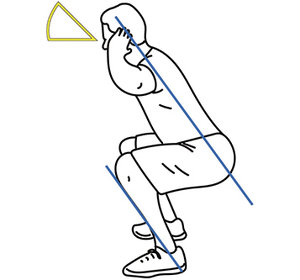

Figure 1

After verbal cueing, proceed to tactile cueing for more stimulus until the patient has a solid understanding of the intended movement pattern. If internal and external cueing do not resolve the movement deficit, then proceed with corrective exercises, soft-tissue work and CMT as mentioned above.

Figure 1

After verbal cueing, proceed to tactile cueing for more stimulus until the patient has a solid understanding of the intended movement pattern. If internal and external cueing do not resolve the movement deficit, then proceed with corrective exercises, soft-tissue work and CMT as mentioned above.

Sight of Gaze and the Spine

In the upper-body domain, common postural imbalances DCs treat, such as a head tilt, anterior head carriage or high shoulder, are also observed while performing the BSA and are managed just as you would any patient. Thus, they will not be discussed here. However, I will address the deficits created by disassociation between the sight of gaze and the spine.

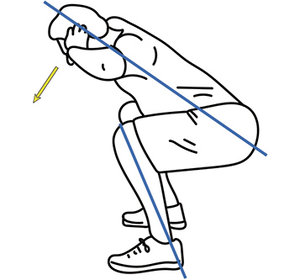

Figure 2

Specifically, athletes frequently hyperextend the cervical spine when they "look up." This faulty movement pattern can often be corrected by placing a bean bag on the top of their head or using the cue, "Keep your chest up," instead. In general, a neutral to slightly upward gaze is preferred. (Fig. 1) A downward gaze is discouraged since a significant increase in hip and trunk flexion is observed when squatting with a downward gaze. In fact, squatting with a downward gaze can increase trunk flexion by up to 4.5 degrees, which places increased load on the lumbar discs. (See one of my previous articles, "Low Back Rehab Exercises: Maintaining Neutral Spine,"for details.) It also disrupts the tibia-torso line relationship. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2

Specifically, athletes frequently hyperextend the cervical spine when they "look up." This faulty movement pattern can often be corrected by placing a bean bag on the top of their head or using the cue, "Keep your chest up," instead. In general, a neutral to slightly upward gaze is preferred. (Fig. 1) A downward gaze is discouraged since a significant increase in hip and trunk flexion is observed when squatting with a downward gaze. In fact, squatting with a downward gaze can increase trunk flexion by up to 4.5 degrees, which places increased load on the lumbar discs. (See one of my previous articles, "Low Back Rehab Exercises: Maintaining Neutral Spine,"for details.) It also disrupts the tibia-torso line relationship. (Fig. 2)

Excessive Trunk Flexion

Excessive trunk flexion (Fig. 2) can be related to other imbalances besides a downward gaze. The muscular dysfunctions suspected in excessive trunk flexion are related to an imbalance between the hip flexor and posterior chain complexes. Today's sedentary lifestyle, in conjunction with activities such as cycling and running, encourage a pattern of flexion dominance which will manifest as an increase in trunk flexion with squat assessment. Probable restrictions, weaknesses and corrective actions are listed in the Table.

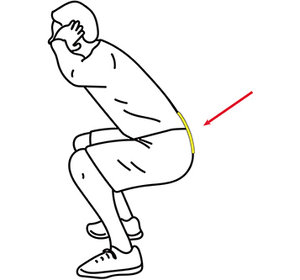

Figure 3

Excessive Lumbar Extension

Figure 3

Excessive Lumbar Extension

Excessive lumbar extension is another deficit observed during the squat. (Fig. 3) It is often an attempt to stabilize the region; however, it places excessive load on the posterior elements and predisposes the patient for injury. Within the lumbar spine, a 2 degree increase in extension (from neutral) increases compressive stress within the posterior annulus on average by 16 percent. Probable dysfunctions and solutions for an increase in lumbar lordosis are listed in the table.

Tip: When lifting heavier loads, a neutral lumbar spine with slight thoracic extension will limit the compressive load on the lumbar spine.

Lumbar Spine Rounding

Another common deficit found in the squat is the "butt wink" or "rounding" of the lumbar spine. (Fig. 4) A loss of the lordosis before 120 degrees of hip flexion indicates restriction in the posterior fibers of the IT band or lack of lumbar control. This is distinct from excessive trunk flexion because the spinal curves are not maintained.

Figure 4

Additional soft-tissue imbalances that create a "butt wink" include tightness in the hamstrings and weakness in the gluteus maximus and intrinsic core muscles. See the table.

Figure 4

Additional soft-tissue imbalances that create a "butt wink" include tightness in the hamstrings and weakness in the gluteus maximus and intrinsic core muscles. See the table.

Clinical Takeaway

Remember, muscles attach to bones, which create movement at joints. While muscular tightness, imbalance and weakness can impact squat mechanics, so can joint dysfunction and loss of motion. Therefore, it is essential that you adjust your patients as needed in correcting deficits in the BSA. Chiropractic physical rehabilitation is the integration of assessment, soft-tissue work, CMT and corrective exercises – all four pillars need to be addressed.

The BSA is a great tool to find movement dysfunctions that impact everyday life and sport. It can be used as a pre- and post-treatment assessment (even on a visit-by-visit basis), as well as a community outreach tool to teach youth athletes proper squat mechanics for injury prevention.

Resources

- Myer GD, Kushner Am ,Bren JL, et al. The back squat: a proposed assessment of functional deficits and technical factors that limit performance. Strength Cond J, 2015 Dec 1;36(6):4-27.

- Kritx M, Cronin J, Haume P. The bodyweight squat: a movement screen for the squat pattern. J Strength Cond, 2009 Feb 31;(1):78-85.

Click here for more information about Donald DeFabio, DC, DACBSP, DABCO.