A century ago, the center of chiropractic was Iowa, but the branches of the profession were spreading out. D.D. Palmer and his fourth wife, Villa, had returned from several eventful years in California,5,13 and had taken up residence at 1518 Rock Island Street (now Pershing Avenue) in Davenport.

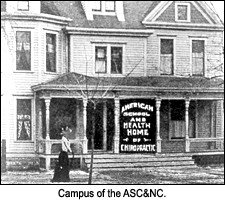

Perhaps even more to D.D. Palmer's chagrin, Langworthy was collaborating with Daniel Riesland, DC, to secure a licensing statute for chiropractors in Minnesota.7 They were successful in having both houses of the state legislature pass the bill, and had only to receive Governor Johnson's signature to make it law. The bill required the applicant for licensure to show graduation from a two-year course in chiropractic, something not yet available at the Palmer School, but offered at the ASC&NC. The Palmers (D.D. and son, B.J.) traveled to the state capital in St. Paul to confer with Johnson, and urged him to veto the bill. Similar sentiments were expressed by the medical community. The governor complied, and it would be eight more years before the first chiropractic statute was passed.11,20

That year also saw an exchange of letters between the elder Palmer and his former legal counsel, Willard Carver, LLB, concerning the inclusion of suggestive therapeutics in chiropractic practice.2 Carver asserted its relevance; Palmer insisted that adjusting subluxations would overcome any deleterious effects "auto-suggestion" might exert upon the nervous system and the general health of the patient. Later that year, Carver enrolled in the Parker School of Chiropractic in Ottumwa, Iowa, from which he would earn his chiropractic degree.9

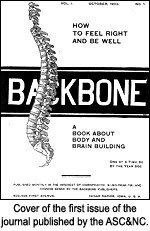

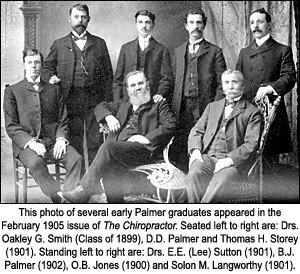

In January 1905, Old Dad Chiro published Volume 1, No. 2 of The Chiropractor, a magazine for chiropractors introduced in response to Langworthy's Backbone. His published assertions for the curative potential of chiropractic care would serve as the basis for his conviction for unlicensed medical practice in Scott County Court the following year.5

A probable stimulus for this trial was an earlier legal entanglement: the death of Palmer's patient, Lucretia Lewis of Oscaloosa, Iowa, an 18-year old tuberculosis patient who spent two days at the Palmer Infirmary before dying.4,15 Ms. Lewis had been referred to Palmer by attorney Carver.

The death at the Palmer Infirmary on 10 March 1905 prompted a coroner's inquest when D.D. signed the patient's death certificate.1 The coroner refused to accept the chiropractor's authority in the matter. Although the three-member jury found that Ms. Lewis died from tuberculosis ("consumption," as it was then often referred to), the inquest brought a number of Palmer's patients, students and the father of chiropractic himself to the stand to explain what chiropractic was all about.19 Palmer was characteristically abrasive in his comments to his allopathic persecutors, a trait that would repeatedly bring him much grief at this time and in years to come. In any case, the father of chiropractic did not disappoint on the witness stand:

Upon another occasion Dr. Palmer addressed the several physicians in attendance at the inquest as follows: "Your patients die every day, but with you there are only two legitimate deaths. One is under the care of an allopathic physicians and the other one on a scaffold with a noose around the neck".19

Before leaving the undertaking establishment, where the inquest was held, Dr. Palmer invited Drs. Lambach, Bowman and Speers down to his infirmary, where he would reveal to them some of the marvels of chiro. But the invitation was respectfully declined.

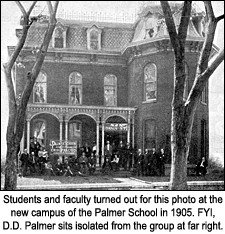

The pages of The Chiropractor also saw more of Palmer's continuing feud with the followers of his Missouri rival, Dr. Andrew Taylor Still, founder of osteopathy. In June, just as the Palmer School was relocating from its first campus to 828 Brady Street,5 D.D. penned the following for his journal:

The Des Moines school [of osteopathy] was the only one that I was ever in. It would not be fair to name my call, of 15 minutes, a visit. That was made in April, 1904 - over EIGHT YEARS AFTER we discovered the first principles of the science of Chiropractic. The Kirksville Osteopath school was then the only one in existence.

Dr. D.D. Palmer Never at Kirksville

The editor of The Cosmopolitan Osteopath cannot bring a witness that will state under oath that he ever saw me in Kirksville, Mo., or in the Osteopath school of that place. Now, Mr. Editor, I emphatically state, that I never was in Kirksville, Mo., have never even passed thru that town. If you will be kind enough to back up your statement with the names of one or more persons who saw me there, I feel that you have done me justice.

I am tired of following up these lying whelps. But self-preservation demands that I shall down all these untruthful statements.16

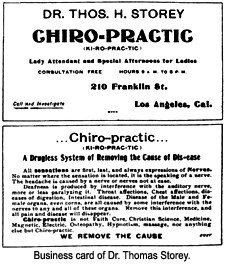

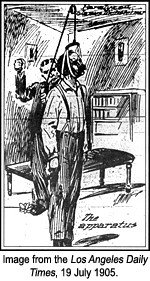

Meanwhile, Palmer's former student, Thomas H. Storey, DO, DC, of Los Angeles, was arrested for practicing medicine without a license.8,18 Dr. Storey is perhaps best remembered as the father of instrument adjusting and as mentor to Charles A. Cale, DC, ND, founder of the Los Angeles College of Chiropractic.13 In 1905, Storey was charged when a patient was paralyzed, apparently due to his use of cervical suspension traction and electrotherapy. He was found guilty of unlicensed practice in July, and was fined $500. The patient later died, but Dr. Storey continued in practice.18

While Palmer in Iowa and Storey in California struggled with the medical and legal communities, two self-designated "chiropractics" in LaCrosse, Wisconsin went on trial for practicing without licenses. D.D. Palmer traveled to the Mississippi river town to testify on their behalf, but was not permitted to take the stand, on the grounds that he was not a Wisconsin resident.14 Nonetheless, he used the occasion of his visit to upbraid the two men about their use of modalities.3 The pair, G.W. Johnson and his partner, E.J. Whipple, would face repeated prosecutions at the behest of Wisconsin's osteopathic community; their travails provided backdrop for the 1907 trial and acquittal of Shegetaro Morikubo, DC, charged with practicing osteopathy without a license.17

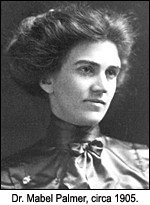

Mabel Heath Palmer earned her chiropractic degree in 1905, and served as manager of the day-to-day activities at the Palmer School. She had married B.J. on 30 April 1904, and spent much of the next year in a "family way": David D. Palmer, future president of the Palmer School, was born 12 January 1906. Meanwhile, D.D. Palmer's ailing wife, Villa, died on 9 November 1905 of a morphine overdose. The local authorities once again called for an inquest, and once again Old Dad Chiro was exonerated, although he had provided the self-administered dose to his wife. And by this time, the father of chiropractic had again been indicted (as he had been in Pasadena, California, in 1902) for the unlicensed practice of medicine.5,10

It was a year of tragedy and legal strife for the Palmers and the small but growing chiropractic profession. And soon, the father of chiropractic would experience conviction, jailing, departure from Davenport and separation from the school he founded.10 One hundred years ago, the seminal figure in the chiropractic saga was between the proverbial rock and a hard place, and chiropractors were beginning to feel the sting of the law. It was the start of a long trail of persecution and prosecution.

References

- Both inquest and autopsy. Davenport Democrat & Leader, 10 March 1905, p. 9.

- Carver W. Letter to D.D. Palmer, 15 February 1905. Reproduced in Journal of the National Chiropractic Association 1958 (Oct);28(10):9-10, 52, 54.

- Chiropractic versus osteopathy. The Chiropractor 1905 (Oct);1(11):21-3.

- Coroner's jury brings in verdict that death was natural and without criminal contribution. Oscaloosa Times, 13 March 1905, p. 2.

- Gielow V. Old Dad Chiro: A Biography of D.D. Palmer, Founder of Chiropractic. Davenport, IA: Bawden Bros., 1981.

- Gibbons RW. Solon Massey Langworthy: keeper of the flame during the "lost years" of chiropractic. Chiropractic History 1981;1:14-21.

- Gibbons RW. Minnesota, 1905: who killed the first chiropractic legislation? Chiropractic History 1993 (June);13(1):26-32.

- Hot after doctor. Los Angeles Daily Times, 19 July 1905, p. 1.

- Jackson RB. Willard Carver, LL.B., D.C., 1866-1943: doctor, lawyer, Indian chief, prisoner and more. Chiropractic History 1994 (Dec);14(2):12-20.

- Keating JC. BJ of Davenport: The Early Years of Chiropractic. Davenport, IA: Association for the History of Chiropractic, 1997.

- Keating JC. Barely legal. Chiropractic History 2002 (Winter);22(2):59-64.

- Keating JC, Callender AK, Cleveland CS. A History of Chiropractic Education in North America: Report to the Council on Chiropractic Education. Davenport, IA: Association for the History of Chiropractic, 1998.

- Keating JC, Phillips RB (Eds): A History of Los Angeles College of Chiropractic. Whittier CA: Southern California University of Health Sciences, 2001.

- Keating JC; Sportelli, Louis; Siordia, Lawrence. We Take Care of Our Own: NCMIC and the Story of Malpractice Insurance in Chiropractic. Clive, IA: NCMIC Group, Inc., 2004.

- Lerner C. Report on the History of Chiropractic. Unpublished manuscript (circa 1954) in eight volumes (Lyndon E. Lee Papers, Palmer College Archives).

- Palmer DD. The Chiropractor 1905 (June);1(7):14.

- Rehm WS. Legally defensible: chiropractic in the courtroom and after, 1907. Chiropractic History 1986;6:50-5.

- Smith BA. Thomas Henry Storey, D.O., D.C., 1843 to 1923. Chiropractic History 1999 (Dec);19(2):63-84.

- Verdict returned upon death of Lucretia Lewis. Davenport Democrat & Leader, 12 March 1905, p. 5.

- Wardwell WI. Chiropractic: History and Evolution of a New Profession. St. Louis: Mosby, 1992.

- Zarbuck MV. Historical naprapathy. Illinois Prairie State Chiropractic Association Journal of Chiropractic 1987 (Jan);8(1):6-8.

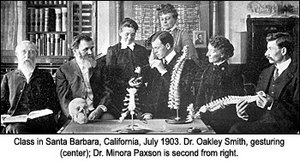

- Zarbuck MV. Oakley Smith, DC (1880-1967), "Bohemian chiropractic" and the evolution of naprapathy. Journal of the American Chiropractic Association 1997 (May);34(5):66-72.

Joseph Keating Jr., PhD

Phoenix, Arizona

Click here for previous articles by Joseph Keating Jr., PhD.