A healthy self-esteem is also based on whether you perceive yourself as a success or failure. If you have a flourishing practice, and your patients are forever blessing you for your help, chances are your self-esteem as a doctor is high and free from doubt.

Our professional, self-fulfilling prophecy began when we decided to pursue a career in chiropractic. Our preconceptions of what life as a chiropractic doctor would be like definitely helped shape that prophecy. Our teachers in chiropractic college served as models of things to come. How they looked, acted, and talked constituted the building blocks, the guideposts leading to our individual prophecy.

To reiterate, your professional persona derives from how you see yourself, how others see you, how you think others see you, and how you would like to be seen by others. Each plays an integral part in your image as a health care giver. Some doctors treat their patients in a conventional shirt and tie, others wear white coats, presenting themselves according to their conception of how a doctor should look. The reflection in your mirror is not necessarily the one your patients see. What you say to your patients, how you say it, and how you look when you say it, each reveals something about your character and personality.

From childhood, you develop a repertoire of roles. In fact, it might be argued that your "real self" does not exist apart from the roles you play; your real self is simply a composite of the various roles you have learned to play. You may also discover that you are more comfortable playing certain roles more than others.

Playing the role of doctor represents only part of your life. You may also play the parent role with your children, the husband or wife role with your spouse, and still another role with your close friends. This is perfectly normal behavior. Problems may arise when your roles become confused or they emerge inappropriately. An example would be treating your family members as if they were patients, not your loved ones, or becoming overly friendly with your patients.

Differentiating between your personal and professional identity is important. Should the self you present at a neighbor's wedding reception, or at a party among personal friends be different than the one you present to your patients? The answer must be yes. Liberties taken among friends are decidedly different from those taken with patients. A doctor, with impunity, may ask a female patient about her menstrual cycle. Such questioning would be totally inappropriate during a conversation over cocktails.

Years ago, doctors socialized with doctors and, on occasion, with nurses and other members of the medical profession. This insulated them from the embarrassment that might have resulted from an indiscrete remark, or some socially unacceptable behavior.

Times, however, have changed. Professionals now mix more freely in society. The aloofness that once prevailed with the healing arts has diminished. The invisible barrier which once caused the layman to be in constant awe of doctors has substantially diminished. Patients are no longer intimidated by doctors; doctors can no longer hide behind the inviolate image they once enjoyed.

Each of your patients perceives you a little differently. Despite the fact that what they say about you very often says more about them, you should not dismiss what they say out of hand, particularly if there is a shared opinion. Nurses and technicians are frequently privy to opinions that never reach your ears. Since you and your staff should think of yourselves as a team, it is essential that judgmental remarks made by patients (favorable and unfavorable) be shared. Then if your image is in jeopardy, you can do something about it.

Preconceptions by a new patient also warrant your attention. Someone who has never had chiropractic before or has been soured against chiropractors by a medical practitioner, might perceive you from the outset as not being a "real doctor." You, in turn, might react differently because of the patient's negative attitude. Not unsurprisingly, doctors and patients constantly feed one another messages that either confirm or deny what they already think. To be sure, any one of these messages has the potential of contributing to or detract from a doctor's self-image.

Psychologist Carl Rogers maintained that the only way to develop a fully functioning self is to be open to new ideas and experiences. The operative word is "openness." Close-mindedness erects walls, not bridges, to a healthy and realistic professional persona. A shortcut to achieving such a goal is to search out a doctor whom you perceive to have such an image and imitate him. Rest assured, this will not compromise your innate self. Think of it as behavior modification or modeling. While retaining your individuality, adjust your thinking and behavior to conform with that of the doctor whom you most admire.

A distorted view of yourself will prevent you from seeing your patients clearly. If you have a negative attitude toward yourself, you may be negative about everything because your self-concept filter causes you to perceive incoming messages negatively. During any treatment period, your patients continuously send you verbal and nonverbal messages as indicators of how they are doing. Your responsiblity as doctor is to decode these messages. A warped self-image on your part could, with a high degree of probability, misinterpret the meaning of these messages.

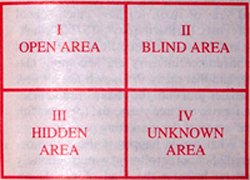

The next time you look in a mirror, seriously ask yourself this question, "What makes me feel like a doctor?" Is it simply because I have a diploma on the wall, that people address me as doctor, or because people who are sick come to me? Aside from these obvious reasons, can you think of any others? Perhaps the following diagram will help. It is called the Johari Window:

As you can see, the Johari Window consists of four boxes. Box #1 is the open area which contains information that is known to you and to others (name, age, religious affiliation, or food preferences). Box #2, the blind area, contains information about you that others know, but you don't know (faults or virtues). Box #III is your hidden area containing information you know about yourself, but do not want others to find out (wife beater, cheat on your taxes). Box #14, the unknown area, contains information about which neither you nor others are aware (an undiagnosed birth defect, an aptitude for drawing). Ideally, successful patient management on the part of a "real" doctor should strive to increase the size of the open area and decrease the size of the blind, hidden, and unknown areas.

Your reputation is, perhaps, the best clue to your professional persona. Do people in your neighborhood, town, or village use any of the following adjectives to describe you: kind, gentle, available, greedy, thorough, intelligent, attractive, competent, patient, sloppy or indifferent? Most doctors have only a vague notion of how they are actually being perceived. Unfortunately, how we see ourselves is generally subordinate to the more self-serving aspect of our psyche, and less so to external indicators.

In the sum, the professional persona of a doctor is not invariant. Each of us has the ability to alter that image. We are privileged with an opportunity to borrow information about ourselves learned from the past, correlate it with information from the present, and, with a little imagination, creativity, and courage, give birth to a new and more vibrant professional persona -- one of which not only you can be proud, but one which will make us all proud to be doctors of chiropractic in a rapidly changing world.

Abne Eisenberg, D.C., Ph.D.

Croton on Hudson, New York

Editor's Note:

As a professor of communication, Dr. Eisenberg is frequently asked to speak at conventions and regional meetings. For further information regarding speaking engagements, you may call (914) 271-4441, or write to Two Wells Ave., Croton on Hudson, New York 10520.