We approach the barrier with a whole different style and attitude. Instead of pushing in deeply, we place our hand over the area and sink in to get the sense of the layer we want to assess. Instead of poking or prodding, we let the information in. Our initial touch is what you would use with a newborn: gentle and "listening." Our intent is to "receive" from the tissues. We are not attempting to change anything yet, just to take in. The tissues are an incredible storehouse, embodying the traumas experienced; the postures habitually adopted; the fascial memory.

Palpation is an interactive skill. It's a relationship between your hands and the patient's body. The soft touch allows the tissues to give you more feedback; to get a deeper sense of the twists and torques stored in the tissue.

This will be a new psychomotor skill for most of you, or at least a variation of what you have been doing. To learn this, you must practice on thousands of patients and build your internal database. I will readily admit that this skill took me a long time to master. My default, especially when I am confused or beginning to learn a new manual skill, is to push harder. I have had to constantly remind myself to back off, to soften my hands.

Barrier Palpation: What is Initial Response Testing (IRT)?

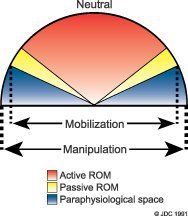

Motion palpation teaches us to take a joint through its range of motion to the end of the physiological range. Framework practitioners prefer a different type of motion palpation. We engage the segment in the direction we are interested in, starting from static neutral, and move just a millimeter or two. We feel for the initial sense of the barrier, which does not require us to be at the end of the physiological range of motion. We are not really feeling for motion: We are feeling for a normal "give" vs. a feeling of stiffness. This method is simple, quick, and noninvasive.

The Joint Barrier

First, as you sink in, your listening hands can get a sense of tissues far below the surface. More superficial tissues become like windows, transparent structures that we can feel through. The joint restriction is reflected toward the surface, affecting all of the tissues in the region but focused at one spot. You know this feeling: A whole area will be very tight, but a more precise palpatory analysis will allow you to find one segment that is tightest.

Think of the barrier as a hologram. Imagine that all the information it contains, all of the mechanoreceptor neurological connections, can be accessed at the very beginning of the your engagement of the tissue barrier.

Just Enough Force for Assessment - and the Adjustment

The key is to be able to feel the beginning of the restriction. Don't push all the way to the hard, locked far edge of the barrier. See if you can feel the barrier as it begins to build against your pushing fingers. As chiropractors, we tend to think of our pressure as going right up against the physiological limit of motion. We tend to be somewhat harsh in our palpation, which correlates with our usual method of treatment: the high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust.

George Roth, developer of tensegrity, advises: "To the barrier, not through the barrier." You will get more accurate information as you use "just enough" pressure in your palpation. The body will respond much more easily if you use "just enough" force for your adjustment, whether it's low-force or a high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust. Yes, this same principle can be applied to your usual adjusting, and to our low- force techniques. Low-force adjusting techniques are most effective at this early point in the barrier. Our low-force-framework adjustive techniques, which include muscle energy (postisometric relaxation aimed at the joint), recoil and ELF (engage, listen, follow), all work at this level, the "feather edge" of the barrier.

Getting Practical: How to Assess Using IRT

Your initial scan is ideally done with an open hand, using your palm or your whole hand. Sink slowly into an area, either directly over the midline of the spine, or paraspinally. Once you've found a restricted area, you can use your thumb pad, or your finger pads to get more specific. Keep your hands soft; don't poke.

To be more specific, you can do one of two approaches. One would be to assess flexion vs. extension, L rotation vs. R rotation; and L lateral bending vs. R lateral bending. We've now defined the three dimensions of the restriction. These can all be done either at the spinous process, or out laterally over the lamina or transverse processes. Again, all of these can be done without going all the way to the end of the motion. This is not traditional motion palpation! We can assess with the patient sitting or prone.

Another approach here is just to sink into the barrier in a "3-D" way. This is harder to explain. My hands are just seeking the direction of restriction as I sink in; my mind figures it out after my hands already have found the exact direction.

If the methods described above are a stretch for you, try this: For those who are used to pushing aggressively right to the barrier, it may be easier to push to your usual depth and then back off. Initially, back off a little, and gradually back off more and more. You will find that you can still accurately feel the restriction at an earlier point.

Do I ever push in more deeply? Yes. When I want to use tenderness as my "reality check," I'll push in as deeply as I need to over the restricted area to elicit pain. This may be quite deep on someone with a high pain tolerance. I often find that one side or the other of the spinous process will be quite tender, a more easily accessible structure for my tenderness "reality check."

I recognize that I've hammered on one idea for the last 1,167 words here. But this is the most important concept for manual low-force palpation and adjusting. Soften your hands; feel for the earliest changes; and use just enough pressure. Try this out, and see how it changes your sense of the restricted segment - the subluxation.

References

- Rex L. Introduction to muscle energy techniques, (course notes), Edmonds, Wa., Ursa Foundation; 1996. p. 244-249.

- Lien Mechanique (Mechanical Link), Paul Chauffour, 1986.

- Mechanical Link courses, levels 1-4, Paul Chauffour, 1996-2001.

- Visceral manipulation courses, Upledger Institute, 1996-2001.

- Visceral Manipulation, Jean-Pierre Barral, Eastland Press, 1988.

- Principles of Manual Medicine, 2nd edition, Philip Greenman, Williams and Wilkins, 1996.

- Manipulative Therapy in Rehabilitation of the Locomotor System, Karel Lewit, Butterworth, Heinemann, 1991.

Click here for more information about Marc Heller, DC.