My initial article in this series [January issue] introduced the unloaded Back Squat Assessment (BSA) as a foundational exercise for both sport and ADLs, and reviewed the standardization of the BSA as an assessment tool. The follow-up article [March issue] detailed common deficits found in the upper domain of the body during the BSA, as well as proposed corrective actions. Building on those articles, let's now discuss common deficits seen in the lower domain (i.e., hips, knees, ankles and feet) while performing the BSA and corrective actions you can take to help your patients.

Before You Begin Your Evaluation

Although we are deconstructing a foundational exercise into domains and isolated movement patterns, it is essential to remember the squat needs to be assessed in its entirety. The most significant imbalances within the entire kinetic chain will be the starting point for your intervention and treatment.

Consistent with our chiropractic principles, correction of the underlying cause of any deficit is the objective and will be any combination of the following:

- Lack of understanding the movement skill requested

- Neuromuscular imbalance: lack of coordination

- Muscular stability issue: weakness or tightness

- Joint dysfunction

Therefore, as you evaluate your patients, be thoughtful as to why they present with a dysfunctional movement pattern so the appropriate corrective action can be instituted. First, review the knowledge of the skill requested. Second, investigate the neuromuscular component. Third, assess muscular weakness and tightness. And of course, fourth and by no means last, always be sure to assess for joint dysfunction and adjust the patient as needed, including extremities.

Therefore, as you evaluate your patients, be thoughtful as to why they present with a dysfunctional movement pattern so the appropriate corrective action can be instituted. First, review the knowledge of the skill requested. Second, investigate the neuromuscular component. Third, assess muscular weakness and tightness. And of course, fourth and by no means last, always be sure to assess for joint dysfunction and adjust the patient as needed, including extremities.

Once aberrant movement patterns are identified, a combination of verbal cueing, compensatory assistance and resistance techniques are applied for correction. Compensatory assistance differentiates from verbal cueing because it uses an external physical stimulus to help retrain the movement pattern; e.g., holding a dowel vertically along the spine to maintain neutral spinal curves during descent and ascent.

External resistance is used to promote strength and stability and to make an individual more aware of their technique. In general, improvement in mechanics with external resistance implies neuromuscular deficiency or lack of understanding of a desired movement pattern to be the most probable cause of the limitation (for example, placing an elastic band above the knees to force the patella to track over the foot and avoid a valgus knee shift).

Hip Deficits

The dysfunctional movement pattern in the BSA for the hip region discussed by Meyer and Kushner is dropping of one hip in the frontal plane. This indicates neuromuscular deficiencies, although mobility restrictions that prevent hip flexion, knee flexion or ankle dorsiflexion will all contribute to frontal plane asymmetries of the hip. This highlights the importance of adjusting these areas. Common imbalances and corrective actions for frontal plane imbalances in the hip are listed in the chart.

Clinical Tip: Lack of great toe dorsiflexion can also contribute to frontal plane imbalances in the hip and will appear as a shift to the opposite side.

Knee Deficits

Frontal plane imbalances in the knee with the BSA are easily observed. The knee is expected to track directly over the foot, with the center of the patella tracking over the first and second toes. Shifting of the knee into valgus is common and generally due to poor understanding of proper squat mechanics or a neuromuscular imbalance of quadriceps and adductor dominance. Varus shift of the knees, while less common, is often a neuromuscular deficit, but can also be a compensatory mechanism for athletes with flat feet. See the chart for examples on treatment for both knee valgus and varus shifting.

Clinical Tip: Be sure to check jumping and hopping mechanics (dynamic loading) for valgus and varus shift of the knee in your athletes and weekend warriors.

Tibial Deficits

As we move down the kinetic chain, Meyer and Kurshner assess the tibial translation angle next. This is essentially the extent to which the knee travels past the toes at the bottom of the descent.

An increased anterior tibial translation, whereby the knees travel far past the toes at the bottom of the squat, does increases torque about the knee. However, they point out that "there is no known evidence that a defined point exists whereby injury risk exceeds the potential benefits during the squat exercise. Moreover, a conscious effort to restrict forward translation has been shown to increase forward trunk lean, resulting in significantly greater forces at the hip and spine that place these joints at greater risk of injury."

In evaluating tibial translation, your take-home points are the following:

- The feet remain flat on the floor

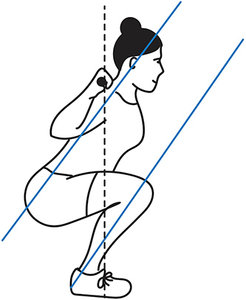

- The tibia angle needs to approximate the torso angle during the entire squat. (See figure)

Clinically, maintaining the tibia / torso lines parallel and preventing excessive anterior tibial translation is frequently related to mobility issues in the ankle and feet in conjunction with weakness in the gluteal and hamstring complexes. Again, refer to the chart.

Clinical Tip: Be sure to check hip hinge mechanics, as proper hip drive is essential to maintain the tibial translation angle.

Foot Deficits

The final lower-domain region to assess is the feet. Perhaps the most common deficit in the feet is elevation of the heels off the ground. This indicates tightness in the soft tissues of the ankle and lower leg, and lack of motion in the foot and ankle. Again, this is another dysfunction that needs to be adjusted when present to achieve normal squat mechanics. Of course, any excessive rolling in or out of the foot would be considered abnormal movement as well. Corrective procedures are found in the chart.

Clinical Tip: Body weight should be through the heel and lateral foot while keeping the toes on the ground. Shifting weight toward the back of the foot facilitates hip drive, and having weight on the lateral foot encourages gluteal recruitment.

Clinical Takeaway

The squat movement pattern is directly related to activities of daily living – whether working out in the gym or getting out of a kitchen chair or driver's seat. Beyond the weight room, teaching good squat mechanics reduces musculoskeletal microtrauma and will benefit all patients.

The final article in this series will discuss squat variations (overhead, single leg, wide stance, heels elevated, etc.) to create various challenges to the kinetic chain, which will allow you to be more specific in developing and progressing exercise prescriptions.

Author's Note: For additional information, I encourage you to watch the Squat Playlist on my You Tube Channel: www.YouTube.com/DrDeFabio.

Resources

- Myer GD, Kushner Am ,Bren JL, et al. The back squat: a proposed assessment of functional deficits and technical factors that limit performance. Strength Cond J, 2015 Dec 1;36(6):4-27.

- Kritx MA, Cronin J, Haume P. The bodyweight squat: a movement screen for the squat pattern. J Strength Cond, 2009 Feb;31(1):78-85.

Deficit |

Probable Tight Muscles & Joint Restrictions (CMT Needed) |

Probable Weak Muscles |

Suggested Corrective Actions |

| Hip: Unilateral Drop | Side of elevation: Quadratus lumborum TFL Gluteus medius (weakness) Lack of hip, knee or ankle mobility |

Side of drop: Overall leg strength inequality Weight shifted to “strong” leg Excessive foot collapse Excessive foot turn-out |

Verbal cueing Single-leg squats Split squats Bosu squats Video analysis CMT Hip flow routines |

| Knee: Shift Into Valgus | Adductors TFL Quadriceps Loss of hip mobility Loss of ankle dorsiflexion |

Gluteal complex VMO Hamstrings Excessive pronation |

Squats with resistance band above knees Jump downs Single-leg ¼ squats |

| Knee: Shift Into Varus | Piriformis Biceps femoris Gluteus minimus Loss of ankle dorsiflexion |

Adductors Medial hamstring Gluteus maximus Poor hip hinge |

Squats while squeezing a ball between the knees Split squats Bridges |

| Excessive Anterior Tibial Translation | Quadriceps dominance Hip flexor complex Limited hip extension |

Gluteal complex Intrinsic Core Poor hip hinge |

Wall squats Sit touches CMT ankle |

| Ankle collapses / Foot Pronates |

Peroneals Lateral gastrocnemius Biceps femoris |

Anterior tibialis Posterior tibialis Medial gastrocnemius Deltoid ligament |

Janda’s short foot Tibialis posterior strengthening Orthotics? |

| Heels Elevate | Soleus Gastrocnemius Ankle mortise |

Anterior tibialis | Lengthen / stretch calves CMT ankle mortise Squats with toes elevated |

Click here for more information about Donald DeFabio, DC, DACBSP, DABCO.