In many respects, universal design serves as the core of ergonomics. It's also a good tool to use when designing a return-to-work program for injured and/or ill patients. Let's take a closer look at universal design and why it should matter to you and your patients.

The purpose of the principles is to serve as a guide in the design of environments, products and communications. According to the NCSU working group, the principles "may be applied to evaluate existing designs, guide the design process and educate both designers and consumers about the characteristics of more usable products and environments."

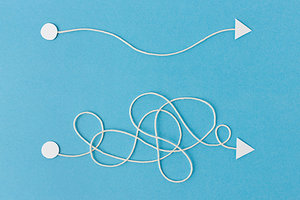

I've always thought of ergonomics as the use of common sense. From a number of vantage points, it makes sense to design products in such a way that more people have access to them, are easy to use and don't create health problems. This can be accomplished by using the seven principles as a road map.

As I mentioned, as a clinician, the principles may also serve as a useful guide when returning injured and/or ill patients to work.

- Equitable use

- Flexibility in use

- Simple and intuitive

- Perceptible information

- Tolerance for error

- Low physical effort

- Size and space for approach and use

Equitable Use: The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities. One of the core components of ergonomics is the desire to make things useful by individuals with a wide range of capabilities (e.g., left-handed individuals or those with vision problems).

This may be done by providing the same means of use for all users (in other words, make things identical whenever possible, equivalent when not); avoiding segregating or stigmatizing any users; providing for privacy, security and safety; and making the design appealing to all users.

Flexibility in Use: The design accommodates a wide range of preferences and abilities. A worker who could lift a 50-pound sack prior to injuring their back may not be able to lift such a load after an injury occurs. Providing some form of mechanical assistance (or lighter loads to lift) would allow them to continue working.

Flexibility may be accomplished by providing for a choice in the methods of use; accommodating right- or left-handed access and use; facilitating the user's accuracy and precision; and providing adaptability to the user's pace.

Simple and Intuitive Use: Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user's experience, knowledge, language skills or current concentration level. The use of touchscreen computers by fast-food workers is a good example. It takes the thought process out of the task, and allows use by people who speak a different language.

I remember eating at a restaurant in Tokyo. Not being able to speak Japanese, I appreciated that the menus had pictures.

Other ways to make things easier / more intuitive include:

- Eliminating any unnecessary complexity

- Being consistent with user expectations and intuition

- Accommodating a wide range of literacy and language skills

- Arranging information consistent with its importance

- Providing effective prompting and feedback during and after task completion

Perceptible Information: The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user's sensory abilities. The strobe lights that are part of smoke alarms allow deaf people to see problems when they occur. Other examples include:

- Using different modes (pictorial, verbal, tactile) for redundant presentation of essential information

- Providing adequate contrast between essential information and its surroundings

- Maximizing "legibility" of essential information

- Differentiating elements in ways that can be described (i.e., make it easy to give instructions or directions)

- Providing compatibility with a variety of techniques or devices used by people with sensory limitations

Tolerance for Error: The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions. This is particularly important in jobs that are inherently dangerous (e.g., construction, electrical work).

Reducing tolerance for error may also be accomplished by:

- Arranging elements to minimize hazards and errors, ensuring the most used elements are the most

accessible, and hazardous elements are eliminated, isolated or shielded - Providing warnings of hazards and errors

- Providing fail-safe features

- Discouraging unconscious action in tasks that require vigilance

Low Physical Effort: The design can be used efficiently and comfortably, and with a minimum of fatigue. This is particularly important during the early return-to-work phase, and can be accomplished by:

- Allowing the user to maintain a neutral body position at all times

- Using reasonable operating forces

- Minimizing the need for repetitive actions

- Minimizing sustained physical effort required

Size and Space for Approach and Use: Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation and use, regardless of the user's body size, posture or mobility. For example, if a worker must use a crutch or cane, the work space should accommodate it.

Other ways to improve adaptability include:

- Providing clear line of sight to important elements for any seated or standing user

- Making reach to all components comfortable for any seated or standing user

- Accommodating variations in hand and grip size

- Providing adequate space for the use of assistive devices or personal assistance

One of the components of the universal design process is to make things accessible to the majority of individuals. This is often referred to as "the 95 percent rule."

Universal Design in Action

- Levers, rather than door knobs that must be turned

- Light switches with large, easy-to-push buttons

- Levers on kitchen and bathroom faucets

- Ramps instead of stairs

- Curb cutouts for wheelchair users and individuals with an unsteady gait

- Flashing lights with security and fire alarms for those with diminished hearing

- Washers and dryers on elevated platforms

- Tub cutouts for easy entry

- The sippy cup

Return-to-Work Utility

I still remember my first worker's compensation patient. He had hurt his back, a not-uncommon experience in the workplace. I kept him off work for a few weeks. When I thought he was ready to return to work, I gave him a lifting restriction that limited him to 10 pounds. I also limited his bending and stooping.

I have no idea whether the restrictions were necessary or helpful. However, if I'd known then what I know now, I probably wouldn't have kept him off work in the first place.

I've since learned that in general, work is healthy and tends to be beneficial. One of my favorite sayings is, "You don't get injured workers well to get them back to work. You get them back to work to get them well."

Today, I would have used the seven principles of universal design as a guide to help me determine what the worker could and could not do while at work. The principles would also have helped me design any accommodations he might have needed.

Click here for previous articles by Paul Hooper, DC, MPH, MS.