Next to osteoarthritis, greater trochanteric pain syndrome is the most frequently encountered hip injury, estimated to eventually affect between 10 percent and 25 percent of the population.1 The patient typically complains of pain with single-leg stance, and the discomfort is often aggravated by side-lying on the affected hip.

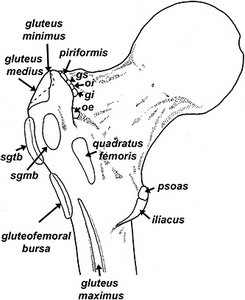

The female to male ratio for this condition is 4:1, and 40- to 60-year-olds are especially vulnerable. This common condition is surprisingly difficult to treat, and symptoms may last months to years. While it was originally believed the lateral hip pain resulted from chronic inflammation in one of the three greater trochanter bursae (Fig. 1), recent research confirms bursal inflammation correlates poorly with the presence of lateral hip pain. As a result, the term greater trochanteric bursitis has been abandoned in favor of greater trochanteric pain syndrome.

To identify the specific tissues responsible for the development of lateral hip pain, Woodley, et al.,2 performed MRI evaluations of the symptomatic and asymptomatic hips in 40 patients presenting with unilateral greater trochanteric pain syndrome. After having the MRIs read by three radiologists, the researchers discovered that although bursal inflammation had no correlation with the presence of lateral hip pain, gluteus medius tendinopathy and atrophy of the gluteus minimus muscle were relatively common and occurred almost exclusively on the side of the symptomatic hip. Because these findings are consistent with other research confirming hip abductor tendinopathy correlates with the presence of greater trochanteric pain syndrome,3 treatment interventions should emphasize restoration of tendon function, not reduction of bursal inflammation.

Fig. 1. Posterior view of the proximal left femur. Sgtb = superfi cial greater trochanteric bursa; sgmb = subgluteus maximus bursa; gs = gemellus superior; oi = obturator internus; oe = obturator externus.

Research-Based Considerations

Fig. 1. Posterior view of the proximal left femur. Sgtb = superfi cial greater trochanteric bursa; sgmb = subgluteus maximus bursa; gs = gemellus superior; oi = obturator internus; oe = obturator externus.

Research-Based Considerations

In an important study comparing the efficacy of different treatment protocols, Rompe, et al.,3 assigned 229 patients with refractory unilateral greater trochanteric pain syndrome to one of three treatment protocols: a single local corticosteroid injection (25 mg prednisolone); a repetitive low-energy shockwave treatment; or a home training program that included specific hip abductor / rotator stretches and exercises as follows, performed twice daily, seven days a week for 12 weeks:

- Piriformis stretch: "Lie on your back with both knees bent and the foot of the uninjured leg flat on the floor. Rest the ankle of your injured leg over the knee of your uninjured leg. Grasp the thigh of the uninjured leg, and pull that knee toward your chest. You will feel a stretch along the buttocks and possibly along the outside of your thigh on the injured side. Hold this stretch for 30 to 60 seconds. Repeat 3 times."

- Iliotibial band stretch (standing): "Cross your uninjured leg in front of your injured leg, and bend down and touch your toes. You can move your hands across the floor toward the uninjured side, and you will feel more stretch on the outside of your thigh on the injured side. Hold this position for 30 seconds. Return to the starting position. Repeat 3 times."

- Straight-leg raise: "Lie on the floor on your back, and tighten up the top of the thigh muscles on your injured leg. Point your toes up toward the ceiling, and lift your leg up off the floor about 10 inches. Keep your knee straight. Slowly lower your leg back down to the floor. Repeat 10 times. Do 3 sets of 10."

- Wall squat with ball: "Stand with your back, shoulders, and head against a wall, and look straight ahead. Keep your shoulders relaxed and your feet 1 foot away from the wall, shoulder-width apart. Place a rolled-up pillow or a ball between your thighs. Keeping your head against the wall, slowly squat while squeezing the pillow or ball at the same time. Squat down until your thighs are parallel to the floor. Hold this position for 10 seconds. Slowly stand back up. Make sure you are squeezing the pillow or ball throughout this exercise. Repeat 20 times."

- Gluteal strengthening: "To strengthen your buttock muscles, lie on your stomach with your legs straight out behind you. Tighten your buttock muscles, and lift your injured leg off the floor 8 [inches], keeping your knee straight. Hold for 5 seconds, and then relax and return to the starting position. Repeat 10 times. Do 3 sets of 10."

Subjects were re-evaluated at one, four and 15 months to evaluate the degree of recovery and severity of pain.

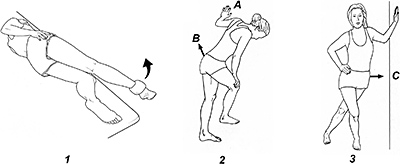

Fig. 2. 1) Gluteus medius home exercises. The side-lying patient is positioned near the edge of a support surface with the involved hip adducted (i.e., the ankle is lower than the support surface). The posterior fi bers of the gluteus medius are exercised by raising and lowering the straight lower extremity through a full range of motion (the hip is abducted and adducted approximately 45° in each direction). To strengthen the gluteus minimus, the same maneuver is performed with the involved hip extended, so the straight lower extremity is hanging off the back edge of the support surface. 2) Gluteus medius stretch. The leg you are stretching is positioned behind you, while the hand on that side is resting against a wall (A). To stretch the gluteus medius muscle, move your hip toward the wall (B). 3) Gluteus minimus stretch. The involved leg is extended while the pelvis is moved toward the wall (C). Your spine should be kept in a midline position while performing this stretch.

Study findings were interesting in that corticosteroid injection produced significant short-term improvements, while shockwave treatment and home stretches / exercises produced better long-term results.

Fig. 2. 1) Gluteus medius home exercises. The side-lying patient is positioned near the edge of a support surface with the involved hip adducted (i.e., the ankle is lower than the support surface). The posterior fi bers of the gluteus medius are exercised by raising and lowering the straight lower extremity through a full range of motion (the hip is abducted and adducted approximately 45° in each direction). To strengthen the gluteus minimus, the same maneuver is performed with the involved hip extended, so the straight lower extremity is hanging off the back edge of the support surface. 2) Gluteus medius stretch. The leg you are stretching is positioned behind you, while the hand on that side is resting against a wall (A). To stretch the gluteus medius muscle, move your hip toward the wall (B). 3) Gluteus minimus stretch. The involved leg is extended while the pelvis is moved toward the wall (C). Your spine should be kept in a midline position while performing this stretch.

Study findings were interesting in that corticosteroid injection produced significant short-term improvements, while shockwave treatment and home stretches / exercises produced better long-term results.

For example, at the one-month mark, 75 percent of the subjects receiving corticosteroid injections reported significant reductions in pain, whereas only 13 percent of the shockwave group and 7 percent of the home exercise group showed significant pain reductions. However, at the four-month follow-up, 68 percent of the individuals receiving radial shockwave presented with significant pain reductions, compared to 51 percent of the corticosteroid group and 41 percent of the home stretches / exercises group. By the 15-month follow-up, the home stretching / exercise group had the best outcomes, with 80 percent reporting significant pain reductions, compared to 74 percent of the shockwave group and 48 percent of the corticosteroid injection group.

The authors state that because the significant short-term superiority of a single corticosteroid injection reversed after one month, "The role of corticosteroid injection for greater trochanter pain needs to be reconsidered."

Your Best Treatment Option

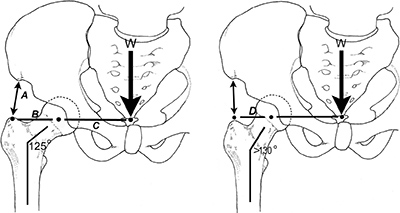

Fig. 3. The typical femoral neck angle of 125° provides gluteus medius (A) an effective lever arm for abducting the hip (B). The longer lever allows the gluteus medius to create the force necessary to oppose body weight (W), which possesses an even longer lever arm for adducting the hip (C). When the femoral neck possesses an angle greater than 130° (i.e., coxa valgum), the lever arm afforded the gluteus medius is significantly diminished (D), thereby limiting the ability of this muscle to stabilize the pelvis in the frontal plane.

Given the economic cost of shockwave therapy, the simplest and most effective method of treating greater trochanteric pain syndrome is with strengthening exercises and stretches. Because the typical greater trochanteric pain syndrome is associated with tendinopathy of the gluteus medius and atrophy of the gluteus minimus, it is important to isolate these muscles with specific stretches and eccentric exercises. (Fig. 2) These exercises are especially helpful when treating individuals with coxa valgum (Fig. 3), since an increased femoral neck angle reduces the mechanical efficiency of the hip abductors and a strong gluteus medius is necessary for injury prevention.

Fig. 3. The typical femoral neck angle of 125° provides gluteus medius (A) an effective lever arm for abducting the hip (B). The longer lever allows the gluteus medius to create the force necessary to oppose body weight (W), which possesses an even longer lever arm for adducting the hip (C). When the femoral neck possesses an angle greater than 130° (i.e., coxa valgum), the lever arm afforded the gluteus medius is significantly diminished (D), thereby limiting the ability of this muscle to stabilize the pelvis in the frontal plane.

Given the economic cost of shockwave therapy, the simplest and most effective method of treating greater trochanteric pain syndrome is with strengthening exercises and stretches. Because the typical greater trochanteric pain syndrome is associated with tendinopathy of the gluteus medius and atrophy of the gluteus minimus, it is important to isolate these muscles with specific stretches and eccentric exercises. (Fig. 2) These exercises are especially helpful when treating individuals with coxa valgum (Fig. 3), since an increased femoral neck angle reduces the mechanical efficiency of the hip abductors and a strong gluteus medius is necessary for injury prevention.

In addition to these exercises, clinical outcomes are often improved by performing deep-tissue massage on the hip abductor and external rotator tendons. To access these tendons, it is often necessary to position the supine patient with the hip abducted 45 degrees. In order to produce the best possible outcomes, the practitioner must be able to isolate each specific tendon near its attachment on the greater trochanter. (Fig. 1)

In my experience, by coupling eccentric exercises with specific deep-tissue massage of the involved tendons, significant reductions in pain occur within the first four months of treatment.

References

- Williams B, Cohen S. Greater trochanter pain syndrome: a review of anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Anesth Analgesia, 2009;108:1662.

- Woodley S, Nicholson H, Livingstone V, et al. Lateral hip pain: findings from magnetic resonance imaging and clinical examination. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2008;38:313.

- Rompe J, Segal N, Cachio A, et al. Home training, local corticosteroid injection, or radio shock wave therapy for greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Am J Sports Med, 2009;37:1981.

Click here for more information about Thomas Michaud, DC.