A wide variety of lower extremity conditions can present to a chiropractor's office: ankle instability, Achilles' tendinitis, patellar tendinitis, to name just a few. The lower extremity functions as a kinetic chain, since faulty mechanics at one joint can predispose other areas to injury.

Foot Biomechanics

The foot must accommodate two distinct functional phases during gait: one is pronation, a mobile phase which allows the sole to adapt to the ground surface; the other is supination, which is rigid and allows for stability during propulsion. Mechanically the entire lower extremity kinetic chain participates in these two phases.1 A number of biomechanical factors representing poor function during one of these two phases can be identified, which often perpetuate common painful syndromes of the lower extremity.

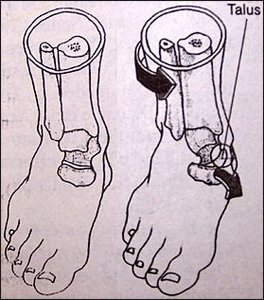

The most common biomechanical problem in the lower extremity is excessive pronation (see Figure 1). This leads to inadequate supination with resultant instability of the entire lower quarter. While the cause of excessive pronation is often difficult to sort out a number of specific factors can be considered necessary prerequisites for supination. These are ankle-joint dorsiflexion to at least 0 degrees; 1st metatarsal phalangeal (MTP) joint dorsiflexion to at least 50 degrees; tibial external rotation; and hip joint extension of at least 10 degrees. For example without sufficient MTP dorsiflexion, the peronei (which attach to the 1st metatarsal) cannot exert the necessary force to shorten the plantar fascia. The plantar fascia shortens, thus approximating the medial calcaneus and 1st MTP and raising the arch. This promotes a stable, rigid foot necessary for supination and a "high-gear" push off.

Figure 1: Subtalar joint pronation causes the talus to adduct and plantarflex.

Mechanism of Injury

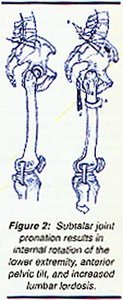

When there is lower extremity dysfunction shock absorption suffers and any joint in the kinetic chain can suffer. Stance phase forces equal 70-80 percent of body weight. During running, forces exceed 200 percent of body weight. Not only lower extremity joints, but lumbar spine facets may also be irritated by faulty mechanics. For instance hyperpronation leads to internal lower extremity rotation, which causes anterior pelvic tilting, and finally repetitive overstress to the lumbar spine in extension (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Subtalar joint pronation results in internal rotation of the lower extremity, anterior pelvic tilt, and increased lumbar lordosis.

The following chart shows how a failure to achieve resupination impacts a number of different conditions.

- Medial overstress of the Achilles' tendon >> Achilles' tendinitis;

- Tibial torsion (internal) >> iliotibial band friction syndrome due to overstretch of insertion on medial tibial plateau;

- Tibial torsion (internal) >> extensor mechanism disorders due to increased lateralization forces of the patellae;

- Internal hip rotation >> anterior pelvic tilt >> facet overload and/or hamstring traction strain.

Evaluation

The following chart summarizes the key joint dysfunctions to look for when treating the lower extremity kinetic chain.

- Ankle dorsiflexion limited to less than 0 degrees.2

- 1st MTP dorsiflexion limited to less than 50 degrees.1

- Hip extension limited to less than 10 degrees.2

Measuring tibial rotation is more complicated, but can also be accomplished during a screening examination. The lower leg can be measured in its functional position during the stance phase of gait by recording the angle of the rearfoot when standing on a single leg. This measurement is shown in Michaud's book.1

The gluteus medius muscle is primarily responsible for stance leg stability. Weakness results in an inability to maintain the body's muscle tightness inhibits its antagonist, the gluteus medius. Once the gluteus medius is weak or inhibited the tensor fascia lata (TFL) typically substitutes for it. This results in increased lateralization forces at the patella and a loss of hip extension mobility. This muscle imbalance can be easily assessed in the sidelying posture by seeing if the thigh flexes during abduction to 30 degrees.3 The only resistance is from gravity.

Treatment

- Adjustment of the stiff joints mentioned above -- 1st MTP, tibia, hip.

- Muscle relaxation -- gastrosoleus, thigh adductors, TFL, iliopsoas.

- Motor control training -- quadratus plantae, peronei, tibialis anterior, gluteus medius.

- External support -- orthotics

References

- Michaud T. Foot Orthoses and Other Forms of Conservative Foot Care. 1996;Newton, MA. (617) 969-2225.

- Yeomans S. Quantifiable Functional Testing Manual & Videotape. 1995; (800) 393-7255.

- Janda V. Evaluation of muscle imbalances. In Rehabilitation of the Spine: A Practitioner's Manual, Liebenson C (ed). Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 1995.

Click here for previous articles by Craig Liebenson, DC.