I lost a friend several months ago. He died from a pulmonary embolism (PE) secondary to a deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) that originated in his lower leg.

Bobby had driven home to see family for Thanksgiving. The trip usually takes 13 hours by car, but Bobby made the trip in just over 11 hours. On the Sunday following Thanksgiving, he began to have trouble breathing and became dizzy when he stood up. He sought help in an emergency room and was diagnosed as being dehydrated, given IV fluids and told not to travel again until he was rehydrated and could stand without experiencing dizziness.

The Tuesday after the ER visit, Bobby woke with labored breathing and asked a family member to call the emergency medical system. He slumped over and died while the call was being placed.

Deep-Vein Thrombosis: Risk Factors and Signs

DVTs form in the lower extremities when blood pools and clots due to prolonged inactivity. Movement is important in lower extremity circulation. The contraction of leg muscles helps pump blood back to the heart. Without muscular contraction, blood flow can stagnate.

DVTs form in the lower extremities when blood pools and clots due to prolonged inactivity. Movement is important in lower extremity circulation. The contraction of leg muscles helps pump blood back to the heart. Without muscular contraction, blood flow can stagnate.

DVTs are a serious problem and can easily lead to death if not detected early and proper treatment initiated. The combination of DVTs and PEs is currently the third leading cause of cardiovascular-related deaths in the U.S., resulting in 100,000 deaths annually.1-2

Table 1 lists clinical circumstances and signs associated with the Wells Score System for DVT probability. Each risk factor has been assigned a value. The sum of the factors relates to the probability of developing a DVT.3 Note that the scale lists paralysis, paresis, being bedridden and immobilization of the lower extremities as factors. All of these factors relate to prolonged inactivity. The same risks are present for traveling long distances with little or no activity during the trip, the same situation described in the story above.

Table 1: The Wells Score System For Dvt Probability

| Clinical Findings | Results |

| Paralysis, paresis, or recent orthopedic casting of lower extremity (1 point) | Desired score = 0 |

| Recently bedridden (more than three days) or major surgery within past four weeks (1 point) |

DVT Risk Score Interpretation 3-8 points: high probability 1-2 points: moderate probability -2-0 points: low probability |

| Localized tenderness in deep vein system (1 point) | |

| Swelling of the entire leg (1 point) | |

| Calf swelling 3 cm greater that the other leg (measure 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity (1 point) | |

| Pitting edema greater in the symptomatic leg (1 point) | |

| Collateral non-varicose superfi cial veins (1 point) | |

| Active cancer or cancer treated within six mo. (1 point) | |

| Alternative diagnosis more likely than DVT (Backer's cyst, cellulitis, muscle damage, superfi cial venous thrombosis, post phlebitis syndrome, inguinal lymph- adenopathy, external venous compression) (-2 points) |

Pulmonary Embolism: A Complication of DVT

The most severe complication of DVT is the development of a pulmonary embolism. PE are life threatening and the possibility of their presence should always be treated as a medical emergency.

The diagnosis of DVT and PE is usually clinical. The patient's history, signs and symptoms usually provide enough information for rendering the correct diagnosis. Once the condition is identified, treatment for a DVT and/or PE must be initiated immediately. Table 2 describes the most common presentations of PE.4

| Table 2: Signs And Symptoms Of Pulmonary Embolism Signs and symptoms of PE may include one of more of the following: • Dyspnea (most common symptom) • Tachypnea (most common sign) • Chest pain • Apprehension • Cough • Hemoptysis • Syncope • Wheezing • Tachycardia • Low-grade fever • Diaphoresis • Leg swelling • Shock |

Does Your Patient Have a DVT? Testing & Differential Diagnosis

Two physical tests can help identify the presence of a DVT: Homan's test and circumferential measurement of calf musculature.5 Homan's test is performed by dorsiflexing the feet individually beginning with the asymptomatic side. As usual, the unaffected side is tested first to establish baseline findings. (In some cases, DVT formation may exist bilaterally, preventing the establishment of baseline findings.) A sharp increase in leg pain with foot dorsiflexion is considered a positive indicator for Homan's test, indicating a DVT.

Homan's test is valuable, but the findings must be differentiated from findings for Braggard's and Fajersztein's tests. Braggard's and Fajersztein's tests are used to detect radiculopathy and sciatica.

All three tests are performed when leg pain is present and all three tests involve dorsiflexion of the feet. The tests are very important in chiropractic differential diagnosis. Braggard's test follows straight-leg raising (SLR) as a confirmatory test. Fajersztein's follows crossed straight-leg raising (CSLR) as a confirmatory test.

SLR and Braggard's tests are considered positive if they cause pain in the symptomatic leg. This is usually considered a sign of irritation to the lateral aspect of the nerve root. Another possibility is that the pain in the symptomatic leg is due to sciatica.

CSLR and Fajersztein's tests are considered positive if their performance using the asymptomatic leg causes pain in the contralateral symptomatic leg. This is usually considered a sign that irritation of the medial aspect of the nerve root is present. CSLR and Fajersztein's tests do not produce pain in the contralateral leg if pain in the symptomatic leg is due to sciatica.

Differentiation of Homan's, Braggard's and Fajersztein's test results is easily accomplished by flexing the knee during Homan's test. Braggard's and Fajersztein's tests depend upon knee extension to help established tension in the nerve roots and sciatic nerve. Flexion of the knee removes nerve root and sciatic tension, allowing more isolation of the calf musculature and deep veins during Homan's test.

It should be noted that occasionally, instructions for performing Braggard's and Fajersztein's tests recommend dorsiflexion of the foot be rapid, snapping the foot back forcefully. This is not recommended here for fear that if a DVT were present, the rapidly applied force could generate emboli.

It is best to dorsiflex the foot slowly and the position be held for a few seconds. It may take a few seconds for radicular or sciatic pain to develop with Braggard's and Fajersztein's tests. Symptoms that develop in response to Homan's test often develop much faster.

Circumferential measurement of calf musculature also requires a degree of differential diagnosis. A DVT creates differences in calf circumferences due to swelling of the involved leg. Radiculopathy and sciatica create differences in calf circumferences due to wasting of the muscles in the involved leg.

Differentiation also can be based on the timing of the conditions. DVT-related circumferential differences in calf size are more acute and develop rapidly. Radiculopathy and sciatic differences in calf size are more chronic and develop slowly. The symptomatic leg is always involved. However, it is increased with DVT, and decreased in radiculopathy and sciatica.

Another important factor for differentiation is that by the time swelling is present from a DVT, the leg will be red and tender to touch. Redness and tenderness are not frequently associated with radiculopathy or sciatica.

High-tech options are also available for diagnosis: diagnostic ultrasound for DVT and pulmonary angiogram for PE.

Common Treatment Options (After You Refer)

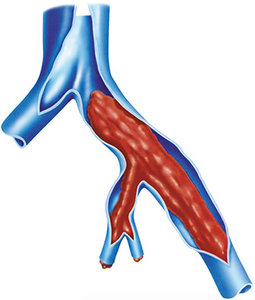

Treatment of DVT and/or PE consists primarily of anticoagulant therapy. A filter also may be implanted in the inferior vena cava to trap emboli before they reach the lungs. Removal of an embolus or pulmonary embolectomy may be required. An embolectomy is especially important in cases in which shock is present.4

Prevention 101: What to Tell Your Patients

Now, having provided a clinical picture of DVT and PE, let's return to the story I began with and the title of this article. While movement to prevent blood from pooling and clotting is not a perfect preventative measure, it could have made a huge difference for Bobby. If he had allotted more travel time and stopped more frequently to move about, he may have avoided death.

The simple advice to all patients: "Take your time while traveling. Stop frequently to walk for a few minutes. Adjust your schedule to prevent long periods of inactivity whenever possible."

Doctors must be aware of the clinical circumstances of DVT and PE for the sake of all patients. The importance of movement as a deterrent for both conditions and for a patient's overall health cannot be stressed enough. All patients must be encouraged to get up and move to the best of their ability, and all doctors must be able to identify DVT and PE in the clinical environment.

References

- Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Rockville (MD): Office of the Surgeon General; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2008.

- Goldhaber, SZ, Bounanmeaux, H. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Lancet, 2012 April 10;379(9828):1835-1846.

- Wells PS, Anderson, DR, Bormanis J, et. al. Value of assessment of pretest probability of deep vein thrombosis in clinical management. Lancet, 1997 Dec 20-27;350(9094):1795-8.

- Catering JM, Kahan S. Emergency Medicine in a Page. Malden: Blackwell, 2003.

- Hoppenfeld S, Zeide M. Orthopaedic Dictionary. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1994.

Click here for more information about K. Jeffrey Miller, DC, MBA.