Dr. Levine was the chairman of the department of chiropractic at the Chiropractic Institute of New York City (CINY) at the time he wrote his book. (Modern-day New York Chiropractic College descends from a different school in New York City, the Columbia Institute of Chiropractic.) Founded in 1944, CINY had 100 students and 10 faculty members in 1967, a year before it disappeared in 1968. In an article in remembrance of Dr. Clarence Weiant, one of the school's founders, Dr. Joseph Keating Jr., writes that CINY was "one of the academically strongest educational institutions in the profession."2

Dr. Weiant wrote the foreword to Dr. Levine's book, and attributed the "mechanical phase" of chiropractic, the concept of vertebral subluxation as the cause of nerve root irritation, to D.D. Palmer. He then related the "static phase" of chiropractic to Willard Carver, DC, for his appreciation of gravitational strain and the interrelatedness of all parts of the human frame. Finally, Weiant awarded the "dynamic phase" of chiropractic to Fred Illi, based on his work on the sacroiliac joint and locomotion, and therefore his contribution to movement analysis.

According to Weiant, this is where Levine's unique contribution arises. Although the mechanical approach of Palmer and the dynamic approach of Illi were alive and well in 1964, the work of Carver had become neglected; his books out of print. Dr. M.J. Rosenthal would write in 1981 that chiropractic structuralism just about disappeared with the death of Willard Carver in 1943.3 Mortimer Levine, said Weiant, had distilled the bare essentials of postural chiropractic from the wildly digressing and somewhat dated work of Carver. In describing his own work, Levine said he "touched on some of the essentials of Carver's work [and] interspersed a thought or two of my own."

Rosenthal distinguished the structural from the segmentalist approach in chiropractic:

"The structural approach to chiropractic analysis held that the human spinal column was a gravity-adapting, weight-supporting structure. Its potential areas of weakness and breakdown, when studied using mechanical engineering concepts, could be readily determined, its advocates claimed. In contrast, the segmental school espoused that vertebrae subluxate in an independent autonomous fashion. The curves of the spine and distortionary patterns were adaptative, natural and normal unless the result of a subluxation which disturbed body balance, its practitioners held."

Throughout most of its history, starting with the Palmers, chiropractic has emphasized segmental subluxations, meaning spinal problems attributed to two adjacent vertebra and the related soft tissues. (This was generalized to include the atlanto-occipital, lumbosacral, sacroiliac, and sometimes the extremity joints.) The segmentalist believes cranial-spinal-pelvic subluxations occur at specific functional units consisting of two bones, be they vertebrae, the skull, any of the pelvic bones, or combinations thereof. Although the subluxation in the specific functional unit may result in postural distortions, such as scoliosis in the frontal plane, and loss or exaggeration of the two kyphotic and two lordotic curves in the sagittal plane, these postural distortions are seen as consequences of specific motor unit subluxations, not as the problems in and of themselves.

Starting with the work of Dr. Carver, the structural approach emphasized spinal regional considerations, and beyond that, the relation of the various spinal regions to one another. It sees postural distortion as the subluxation in and of itself, and offers up a language of listings that describes the linear and angular relationship of entire regions of the cranial-spinal-pelvic articulations. A given functional unit may exhibit more signs and symptoms of dysfunction than another, but this is the consequence, rather than the cause, of the primary postural distortion. For example, the apex of a lateral curvature in the frontal plane may present with more pain, and show more osteophytosis on an X-ray, than the other segments that comprise the curvature. Nonetheless, the curvature, and not its apex, would be the subluxation. The structuralist claims that the spine subluxates as groupings of adjacent vertebrae, and is to be adjusted accordingly, with relatively broad contacts.

Personally, I do not feel the need to choose between segmentalist and structuralist thinking, and in so doing wind up at either of these two extreme positions. It is more likely that individual patients may be better understood as suffering from either segmental or regional complaints. I think a segmental problem is very much affected by the local environment in which it occurs, just as the local spinal environment is partially governed by segmental problems.

Back to Mortimer Levine: His personal effort to rescue the work of Dr. Carver from the dustbins of history failed. On the other hand, the structural approach to chiropractic most certainly did survive, Dr. Rosenthal's protestations notwithstanding, largely because of the seminal work of Dr. Burl Pettibon. Consider it a classic case of parallel evolution. In 1956, Pettibon took the first seminar in upper cervical technique offered by J.F. Grostic. By the 1970s, he had extended that exacting upper cervical analysis to the entire spine. (I think Pettibon, then and now, felt himself upper cervical at heart.) Although Pettibon's roots lie in upper cervical chiropractic, and not the postural approaches of Carver, Logan, or Hurley, he arrives at that same primacy of the postural approach achieved by Carverites such Levine.

As examples of his structural orientation, I will provide two Pettibon citations, three decades apart. Writing in 1972: "We must now discuss the concept of the neck, functioning, not as seven individual bones, but together as a unit of the spine. These bones are intimately related, and thus anything that affects one, affects all."4 Writing in 2001: "Relating the subluxated spine optimally to its environment has to effect the entire spine, and not just a pair of displaced vertebrae."5

Concerning Dr. Levine, how refreshing it is to read his distinction of the "ideal normal" spine, one which is bilaterally symmetric and has normal sagittal curves, from the "practical normal" spine, a spine which is good enough given that "all people have some degree of distortion." This must be contrasted with the overbearing rigidity on the part of some contemporary structuralists who demand a perfectly upright spine and a mathematically defined sagittal configuration. Levine, as Carver before him, understood that a normal posture occurs within a range of values in which function is normal, just like a normal serum glucose level lies within a physiological range of values, rather than constituting a point value.

Levine hated being accused of practicing "general adjusting," as distinguished from the vaunted "specific adjusting." (Four decades later, I feel the same.) He said he was being just as specific in his postural approach as chiropractors using a segmental approach. "As long as an adjusting [sic] is applied according to a corrective hypothesis after analysis of the patient's distortion, that adjusting is specific" (p. 88). For Levine, general adjusting meant using a postural approach to chiropractic; nothing more, nothing less. It was to be judged not according to some petrified, pseudo-philosophical definition of segmental specificity, but on its own merits, according to how its use affected clinical outcomes.

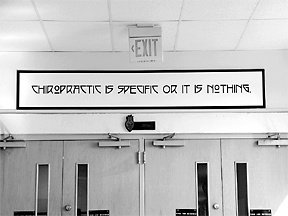

When I visit the Palmer College of Chiropractic in Davenport, I often wind up wandering through the technique labs, which, I insist, are haunted by the spirits of chiropractors past: "Some that you recognize, some that you've hardly even heard of; people who worked and suffered and struggled for fame, some who succeeded and some who suffered in vain" (Ray Davies, Celluloid Heroes, by The Kinks, from their Everybody's in Show Business concept album, 1972). There are signs everywhere saying "chiropractic is specific or it is nothing," a comment attributed to B.J. Palmer himself. That always sends chills down my spine, since in my time, as much as in Levine's, some people think specificity equals segmentalism. Do the ghosts of the PCC technique labs feel betrayed by my chiropractic structuralism? Do they whisper as I walk by, "get him..."?

Offering up yet another interpretation, Levine suggested that for some people, general adjusting meant a full spine approach, whereas specific adjusting was an upper cervical approach. Something tells me that is just what B.J. meant, given his well-known admiration of A.A. Wernsing's masterpiece, The Atlas Specific.6 One of these days, I hope to encounter B.J.'s ghost in one of those PCC technique rooms, and have him confirm for me that the carefully chosen vectors that postural chiropractors use are very, very specific! I know B.J. did not get along well with Willard Carver, but he would have loved the upper-cervical-inspired methods of Burl Pettibon and those who followed in his footsteps!

References

- Levine M. The Structural Approach to Chiropractic. New York, NY: The Comet Press, Inc.; 1964.

- Keating JC, Jr. Remembering Clarence Weiant. In: www.chiroweb.com/archives/18/19/17.html.

- Rosenthal MJ. The structural approach to chiropractic: from Willard Carver to present practice. Chiropractic History 1981;1(1):25-29.

- Pettibon BR. The concept of cervical unit subluxations. Digest of Chiropractic Economics 1972(March/April):48-49.

- Pettibon B. Posture correction and spinal rehabilitation. In: www.worldchiropracticalliance.org/tcj/2001/feb/feb2001pettibon.htm.

- Wernsing AA. The Atlas Specific. Hollywood, CA: Oxford Press; 1941.

Dr. Robert Cooperstein, a professor at Palmer College of Chiropractic West, can be reached at www.chiroaccess.com,or by e-mail at

.

Click here for previous articles by Robert Cooperstein, MA, DC.