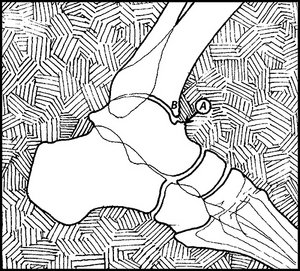

Originally referred to as "athlete's ankle" and later "footballer's ankle" because of the high prevalence in soccer players, this condition occurs when osteophytes on the anteromedial tibia and dorsal talus collide during ankle dorsiflexion, pinching the soft tissues between them (Fig. 1). Over time, the inflamed tissues hypertrophy and the potential for soft-tissue entrapment worsens.

Although early research suggested the osteophytes form in response to excessive tractioning of the joint capsule associated with repetitive ankle plantarflexion, Tol, et al.,1 proved that traction injury is not the cause, because talar and tibial osteophytes do not form at the capsular attachment points. Their cadaveric dissections confirmed the hypertrophied soft tissues in the anterior ankle form in response to tibial and talar bony surfaces being pinched with repeated ankle dorsiflexion.

In sports such as soccer, repetitive contact with the ball produces a thickening of the soft tissues in the anterior ankle, increasing the potential for impingement with repeat ankle dorsiflexion. Massada, et al.,2 note that 60 percent of all professional soccer players present with anterior ankle osteophytes. Anterior ankle osteophytes are also common in sports requiring excessive ranges of ankle dorsiflexion, such as ballet and competitive race walking.

FIG 1 Impingement exostoses on the talus (A) and tibia (B).

Athletes presenting with high arches are particularly vulnerable to this injury because they are more likely to suffer inversion ankle sprains, which begins a cycle in which the sprain itself may lead to a tearing of the anteromedial capsule, eventually resulting in cicatrization of the capsule and the synovial lining. If the anterior talofibular ligament is damaged, the excess talar adduction associated with this injury will force the medial facet of the talus to jam into the medial malleolus.3 The repeat compression eventually leads to a pinching of the anteromedial soft tissues surrounding the capsule.

FIG 1 Impingement exostoses on the talus (A) and tibia (B).

Athletes presenting with high arches are particularly vulnerable to this injury because they are more likely to suffer inversion ankle sprains, which begins a cycle in which the sprain itself may lead to a tearing of the anteromedial capsule, eventually resulting in cicatrization of the capsule and the synovial lining. If the anterior talofibular ligament is damaged, the excess talar adduction associated with this injury will force the medial facet of the talus to jam into the medial malleolus.3 The repeat compression eventually leads to a pinching of the anteromedial soft tissues surrounding the capsule.

Examination Protocol

Physical examination reveals pinpoint sensitivity over the anteromedial capsule. When the ankle is slightly plantarflexed, the osteophytes on the talus and tibia can be readily palpated. Surprisingly, lateral X-rays only identify approximately 40 percent of the talotibial spurs, because the natural torsion of the distal tibia obstructs direct visualization of the anteromedial tibia.4 To improve radiographic accuracy, van Dijk, et al.,5 recommend oblique radiographs be taken with a 45-degree craniocaudal angle, with the lower extremity externally rotated 30 degrees. The authors demonstrated that oblique radiographs identify 73 percent of the spurs located on the talus and 85 percent of the spurs located on the distal tibia.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for anteromedial ankle impingement syndrome include tenosynovitis of the extensor digitorum longus tendon and anterior tarsal tunnel syndrome. These conditions are readily identified through physical examination: Extensor digitorum longus tenosynovitis produces a palpable crepitus when the ankle is actively dorsiflexed, and may even produce an audible "creaking" when the tendon moves through its inflamed synovial lining beneath the anterior retinaculum.

Entrapment in the deep peroneal nerve can be identified by decreased sensation in the first web space and a positive Tinel's sign over the deep peroneal nerve (it is usually trapped just lateral to the tibialis anterior tendon). In both tenosynovitis and nerve entrapment, shoe lacing should be modified to avoid compressing the anterior ankle tendons beneath the laces traversing the highest eyelets.

Conservative Treatment

Conservative treatment of an anteromedial ankle impingement syndrome is challenging because once the spurs have formed, they are difficult to accommodate.

Heel Lifts: The most common technique to accommodate the spurs is to have the athlete incorporate 10 mm heel lifts to lessen approximation of the distal tibia and talus. Because of their size, the heel lifts should be worn bilaterally.

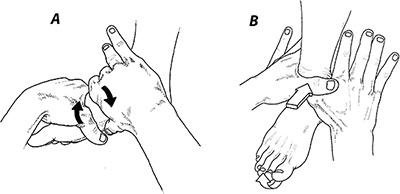

Manipulation: A variety of manual techniques also should be considered to lessen strain on the anterior talotibial articulation and maintain ankle mobility. The manipulation illustrated in Fig. 2A is particularly important in managing this condition because recent three-dimensional research confirms the medial cuneiform can dorsiflex as much as 10 degrees on the navicular.6 By maximizing the range of dorsiflexion available from the midfoot, the navicular / cuneiform joints may absorb motion that might otherwise be absorbed by the talotibial joint.

Fascial Massage: In addition to restoring joint motion, it is also necessary to treat the damaged anterior ankle retinaculum, which is frequently pinched between the tibial and talar osteophytes. As demonstrated by Klein, et al.,7 the anterior ankle retinaculum is comprised of three separate histological layers in which an inner gliding layer rests beneath a thicker middle layer and an outer layer comprised of loose connective tissue containing vascular channels. Fascial massage is thought to enhance gliding of the tendons beneath the inner layer of the retinaculum.

Stecco, et al.,8 emphasize that the anterior retinaculum plays a vital role in proprioceptive awareness. In a recent study, the authors demonstrated that fascial release to the anterior retinaculum results in long-term reductions in pain and improved balance, as measured on stabilometric platforms. Apparently, a damaged retinaculum results in inaccurate proprioceptive afferent innervation, causing impaired coordination and chronic pain.8

Finally, it should be emphasized that if conservative protocols are ineffective, arthroscopic débridement should be considered, since surgical outcomes are excellent: 93 percent of athletes are satisfied two years following surgery and the athlete can return to sport within seven weeks of surgery.9

References

- Tol JL, van Dijk CN. Etiology of the anterior ankle impingement syndrome: a descriptive anatomical study. Foot Ankle Int, 2004;25:382-386.

- Massada JL. Ankle overuse injuries in soccer players: morphological adaptation of the talus in the anterior impingement. J Sports Med Phys Fitness, 1991;31:447-451.

- Umans H, Cerezal L. Anterior ankle impingement syndromes. Musculoskelet Radiol, 2008;12:146-153.

- Tol JL, Verhagen RA, Krips R, et al. The anterior ankle impingement syndrome: diagnostic value of oblique radiographs. Foot Ankle Int.,2004;25(2):63-68.

- van Dijk CN, Wessel RN, Tol JL, Maas M. Oblique radiograph for the detection of bone spurs in anterior ankle impingement. Skeletal Radiol, 2002;31(4):214-221.

- Arndt A, Wolf P, Liu A, et al. Intrinsic foot kinematics measured in vivo during the stance phase of slow running. J Biomech, 2007;40:2672-2678.

- Klein DM, Katzman BM, Mesa JA, Lipton JF, Caligiuri DA. Histology of the extensor retinaculum of the wrist and the ankle. J Hand Surg, 1999;24A:799-802.

- Stecco A, Stecco C, Macchi V, et al. RMI study and clinical correlations of ankle retinacula damage and outcomes of ankle sprain. Surg Radiol Anat, 2011;33:881-890.

- Murawski C, Kennedy J. Anteromedial impingement in the ankle: outcomes following arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med, 2010;38:2017.

Click here for more information about Thomas Michaud, DC.