Starting in the mid 1980s, the so-called "sports medicine" approach began to be applied to chronic back pain patients. Tom Mayer realized that chronic pain patients were deconditioned -- physically and psychologically -- and needed treatment focused on function, not pain, injury or pathology. This has revolutionized the standard of care for all pain patients. Arguments over what type of rehabilitation (i.e., high or low-tech) miss the main point, which is that in painful disorders of the musculoskeletal system, focusing treatment on functional pathology is the key.

What are examples of functional pathology or deconditioning? They can involve various muscles or joints and their mobility, strength, endurance or coordination (i.e., static trunk extensor endurance). Sometimes these are measurable and are called physical capacity tests. Sometimes, as with motion palpation of accessory movement of a joint, they are not measurable and are referred to as dysfunctions. Other examples of deconditioning involve various skills or tasks such as lifting, carrying, climbing, balancing, etc.

Is rehabilitation active care? If rehabilitation is concerned with restoration of function, then by definition it would include both passive and active care. Manipulation of a joint to restore mobility is just as much rehabilitation as back extensor exercises are. Rehabilitation encompasses both passive and active care. The continuum of care with a gradual transition from passive to active care should be considered (see Figures 1 and 2).

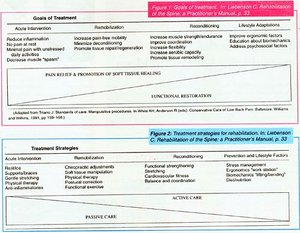

Figure 1: Goals of treatment. In: Liebenson C. Rehabilitation of the Spine: a Practitioner's Manual, p. 33.

Figure 2: Treatment strategies for rehabilitation. In: Liebenson C. Rehabilitation of the Spine: a Practitioner's Manual, p. 33.

Is rehabilitation only for chronics? Generally, in acute care, treatment focuses on stabilization, pain relief and promotion of tissue healing. Once a patient can safely tolerate normal activities of daily living, pain is subsiding, and the inflammation and repair phases of healing are achieved, then treatment goals can transition towards functional restoration. Thus in cases where there is trauma or severe acute pain, rehabilitation would not be a primary goal until the subacute or chronic phase.

If rehabilitation is not for acutes, does that mean McKenzie methods are not rehabilitation? This is an excellent question and a corollary to the preceding paragraph. McKenzie in acute care is for severe pain with muscle splinting and antalgic posture. There is usually pain with many movements and even pain in the mid-range of motions. There can be a distal distribution to symptoms, with rest providing the only relief. Yet this classic derangement syndrome responds very well to self-mobilization to the end range of movement which, through active mobility testing, has been demonstrated to either centralize peripheral symptoms or reduce central ones. Such treatment is clearly active and thus we would assume it is rehabilitative.

At the very least, McKenzie therapy is active self-manipulation of the joints. McKenzie methods are in fact ideal rehabilitation procedures for the acute patient. The determination of the type and direction of treatment is determined by assessing the mechanical behavior of the symptoms. The goal is symptom reduction and improvement in pain-free mobility.

Conclusion

The issue of what is rehabilitation is not as important as that our methods employ active approaches as early as possible, and that we focus our care on functional goals. The era of passive modalities is coming to a close. So is justification for any care including exercise based on pain, injury history or pathological diagnosis.

Craig Liebenson, DC

Los Angeles, California

Click here for previous articles by Craig Liebenson, DC.