Since this muscle group functions over two joints, problems can arise from several sources, and are frequently difficult to deal with.

Another important issue is to improve the functional strength of these vital support and mobility muscles.3 There is some controversy about whether to stretch or strengthen the hamstrings after an acute injury. A recent study has reported on the effectiveness of a frequent static stretching program for athletes after acute hamstring muscle tear.

Hamstring Stretches After Injury

Eighty athletes (52 male and 28 female) were evaluated within 48 hours of suffering an acute second-degree hamstring strain injury.4 Goniometric measurement of active knee extension identified a reduction of 10-15 degrees, and ultrasound images confirmed the acute muscle tear. Initial treatment consisted of PRICE (protection, rest, ice, compression, elevation) for 48 hours.

The athletes were then divided into two groups, both of which performed four standing static hamstring stretches, holding each one for 30 seconds. Both groups were instructed to gradually stretch the injured muscle close to, but not at, the point of pain. Group A did this once daily, while Group B performed the stretching session four times a day. The outcomes measured were the number of days required to regain full knee extension and to return to unrestricted athletic activities.

The researchers found that Group B (who performed a higher volume of stretching) regained normal knee ROM in 5.6 days (versus 7.3 for Group A) and returned to full athletics in 13.3 days (versus 15.0). Their conclusions are that this stretching technique is safe to perform after an acute hamstring injury, and it is most effective when it is done frequently (four times a day).

Functional Hamstring Strengthening

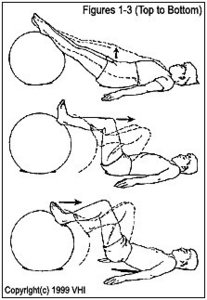

Three strength-building exercises for the hamstrings have been called the "triple threat."5 This protocol targets the hips and hamstrings through similar ranges of motion used in walking and running. Although the supine position of the exercises does not exactly duplicate the posture of running, it closely replicates the horizontal forces on the hips and hamstrings during the stance phase (power stride) of running.

First is the "Bridge," which can be done with the feet up on a step, or on an exercise ball for advanced training. The hips are lifted up from the floor, and then returned in a slow and controlled manner, six times. (Figure 1)

The next exercise is the "Leg Curl," in which the knees are flexed by the action of a strong hamstring contraction, for six repetitions. (Figure 2)

And finally, the "Hip Lift" requires the hips to come up and remain off the floor for the entire exercise, through six repetitions. (Figure 3)

Orthotic Support

During running, the hamstrings are most active during the last 25% of the swing phase, and the first 50% of the stance phase.6 Since this initial 50% of stance phase consists of heel strike and maximum pronation, the hamstrings must control the alignment of the knees and ankles and help absorb some of the impact.

A recent study has shown a significant decrease in electromyographic activity in the hamstrings when wearing orthotics.7 In fact, these investigators found that the biceps femoris had the greatest decrease in activity of all muscles tested, which included the tibialis anterior, the medial gastrocnemius, and the medial and lateral vastus muscles. The researchers theorized that the additional support from the orthotics helped the hamstrings control the position of the calcaneus and knee, and also helped absorb some of the shock of heel strike. Previous studies have demonstrated significant decreases in tibial internal rotation8 and pronation velocity9 when using orthotics.

Conclusion

Acute hamstring injuries require stretching, strengthening and proper support in order to prevent recurring injuries and chronic postural impacts on the pelvis and spine. Effective strengthening and frequent stretching, along with custom-made, stabilizing orthotics (when combined with pelvic and spinal adjustments) are cost-effective treatments with long-term results.

References

- Muckle DS. Associated factors in recurrent groin and hamstring injuries. Brit J Sports Med 1982;16:37-39.

- Jacobs SJ, Berson BL. Injuries to runners: a study of entrants to a 10,000 meter race. Am J Sports Med 1986;14:151-155.

- Johagen S, Nemeth G, Eriksson E. Hamstring injuries in sprinters: the role of concentric and eccentric hamstring muscle strength and flexibility. Am J Sports Med 1994;22:262-266.

- Malliaropoulos N, Papalexandris NS, Papalade A, Papacostas E. The role of stretching in rehabilitation of hamstring injuries: 80 athletes follow-up. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36:756-759.

- Santana JC. Hamstrings of steel: preventing the pull. J Strength Condition 2001;23:18-20.

- Mack RP. AAOS Symposium on the Foot and Leg in Running Sports. St. Louis: Mosby; 1982.

- Nawoczenski DA, Ludewig PM. Electromyographic effects of foot orthotics on selected lower extremity muscles during running. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999;80:540-544.

- Nawoczenski DA, Cook TM, Saltzman CL. The effect of foot orthotics on three-dimensional kinematics of the leg and rearfoot during running. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1995;21:317-327.

- Eng JJ, Pierrynowski MR. The effect of soft orthotics on three-dimensional lower limb kinematics during walking and running. Phys Ther 1994;74:836-844.

Kim Christensen, DC, DACRB, CCSP, CSCS

Director, Chiropractic Rehabilitation and Wellness Program

PeaceHealth Hospital

Longview, Washington

Click here for previous articles by Kim Christensen, DC, DACRB, CCSP, CSCS.