Meralgia parasthetica is probably one of those obscure diagnoses that was learned for the boards and then promptly forgotten once the treatment of "real" patients with "real" conditions began.

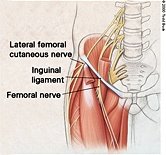

Meralgia parasthetica is defined as the compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, supplied by L2 and L3. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve exits the IVFs of L2-L3 and travels anteriorly and inferiorly, where it crosses underneath the inguinal ligament. This is the most common area of compression, just medial to the anterior superior iliac spine. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is a purely sensory nerve, so the most likely sign of compression will be a patch of sensory loss over the lateral thigh. There may be motor signs in the strength of the tensor fascia lata muscle, with weakness of abduction of the thigh. This is a purely clinical finding that can best be explained due to a loss of sensory bombardment into the dorsal horn secondary to the neuropathy, and a subsequent decreased frequency of firing into the anterior horn.

The decreased central integration locally of the anterior horn decreases the likelihood that the TFL can be brought to threshold, and weakness ensues secondary to the compression. Most texts insist that meralgia parathetica should have no motor component, but clinically, unless I myself am mistaken as to the diagnosis, there is definite weakness that occurs when there is actual compression of the nerve, and measurable and notable changes that occur when treatment is rendered to the nerve at the compression site. The bottom line is that if you find sensory loss related to compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, do not be surprised to find associated muscle weakness, regardless of the reflexogenic mechanisms.

The decreased central integration locally of the anterior horn decreases the likelihood that the TFL can be brought to threshold, and weakness ensues secondary to the compression. Most texts insist that meralgia parathetica should have no motor component, but clinically, unless I myself am mistaken as to the diagnosis, there is definite weakness that occurs when there is actual compression of the nerve, and measurable and notable changes that occur when treatment is rendered to the nerve at the compression site. The bottom line is that if you find sensory loss related to compression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, do not be surprised to find associated muscle weakness, regardless of the reflexogenic mechanisms.

The nerve itself can be damaged due to direct trauma, vascular problems or compression at the inguinal ligament related to weight gain. Many patients will feel worse with activity, and experience some relief with sitting and lying down, confusing the issue for both patients and doctors regarding a muscular cause for their pain. Pain and numbness can be experienced down the side and front of the leg; this also may confuse the issue as to whether it is a lumbar source of pain. Subluxations of the sacroiliac joint can cause a tractioning compression of the nerve, which can further contribute to the confusion of symptoms.

These patients may very well experience significant relief with a good adjustment of the SI joint. However, they also will be the type of patient who will never "hold" their adjustment, and may very well subluxate as they walk out your office. Posturally, secondary to the aforementioned weakness that is common with this compression, the likelihood of a high pelvis on the compressed side is often seen, and it goes without saying that this also would increase the propensity to subluxation of the SI joint and the lumbar spine.

The primary treatment should be directed to the nerve itself, usually directly under the inguinal ligament. Transverse friction massage, as popularized by Dr. Warren Hammer, is an excellent way to minimize the adhesion formations that may be present at the nerve site, usually as a body response to the irritation and inflammation to which the nerve has been subjected. Normally, friction is done perpendicular to the direction of the ligament or tendon, but in this case, due to the fact that the nerve is passing superior to inferior underneath the inguinal ligament, I have found success frictioning across the nerve in a lateral to medial direction - in other words, across the nerve itself.

Nerves are very sensitive, of course, so the treating physician must exercise extreme caution and sensitivity that one treats the area without further traumatizing the nerve itself. Many times, just the friction will be enough to promote an immediate relief of symptoms. Nerve regeneration is a tricky proposition, and according to Dyck in Peripheral Neuropathy, takes about one month for 1 inch of nerve repair to occur. A nerve conduction velocity study, carefully done, may give the treating physician a rough time frame for complete resolution. Personally, I just treat the area and, based on how long it takes to repair, I know how much of the nerve was probably injured to begin with.

Nerve repair requires oxygen, glucose and, most importantly, nerve stimuli. Oxygen and glucose are dependent on a good vascular supply, so checking blood dyscrasias and sugar imbalances is paramount to a successful outcome. Stimulus of the nerve is accomplished through friction massage. In my office, we also use a tens unit or other form of electrical stimuli to pulse the nerve for at least 20 minutes a day. For those of you reticent to use these modalities, remember that the neurological system is in fact an electrical system, so, in my view, we are just helping the body do something it would be doing on its own if it could. If the patient is overweight, then counseling them on how their weight was a contributing factor in their pain may help motivate them to take matters in hand. Finally, once the sensory system is stable and the muscles are strong, a good adjustment likely will keep the ASIS in a more favorable position, and decrease the likelihood that inguinal ligament tractioning and nerve compression will occur. (Another pearl I have picked up over the years treating these compressions: When adjusting the patient in side posture, I only adjust the patient with the compressed side down. This keeps the compressed lower leg extended and minimizes further compression of the nerve.)

I hope this article has helped dissipate the notion that meralgia parasthetica is just a board question for many of us. It is a real condition, with very real consequences to the chiropractic patient. A simple evaluation of sensory and motor systems on the lateral aspect of the leg may very well save the patient many years of pain and suffering that otherwise could have been easily avoided.

Dr. Edgar Romero practices in Miami. He is a diplomate of the American Chiropractic Neurology Board. For questions or comments regarding this article, contact him at

.