As of early April, Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, had estimated that as many as 240,000 Americans will die from COVID-19 infection. Unlike typical seasonal influenzas, in which an affected person typically transmits the virus to 1.3 others,1 an individual infected with COVID-19 will transmit the disease to 2.2 other individuals.2 Fortunately, the vast majority of infected people develop only mild symptoms.

In an exploratory analysis of 44,672 confirmed cases of COVID-19 diagnosed as of Feb. 11, 2020,3 Chinese epidemiologists report that 81 percent of infected patients reported only mild symptoms with no mortality. Another 14 percent developed severe symptoms with no mortality; while 4.7 percent had critical disease with a fatality rate of 49 percent. COVID-19 deaths increased with age, with the fatality rate of 1.3 percent in patients ages 50 to 59, 3.6 percent of patients ages 60 to 69, and 8 percent in patients ages 70 to 79. The worst mortality rate occurred in patients 80 years of age or older, with this group suffering a 14.8 percent mortality rate.

In the first study released from China evaluating 1,099 confirmed COVID-19 cases, severe illness occurred in 16 percent of patients after admission, with 2.3 percent of this group being placed on mechanical ventilators and 1.4 percent dying.4

The Ventilation Dilemma: Weaning Off Can Be Just as Dangerous

Given the fact that millions of Americans are expected to become infected with COVID-19 in the next few months, even if only a small percentage of the population requires aggressive intervention, there will be an unprecedented number of patients requiring mechanical ventilation. As of late March, the governor of New York had said that New York City alone needed 40,000 ventilators in order to adequately treat the affected population.

Ventilators are essential when managing COVID-19, as it gives severely ill patients more time to recover as the machines continue to inflate the person's lungs with air and oxygen.

While mechanical ventilation is a life-saving intervention for those infected with COVID-19, as many as 40 percent of these individuals can experience significant difficulties upon being weaned off their ventilators.5 These patients are more prone to poor functional outcomes and have significantly higher risk for increased mortality.6

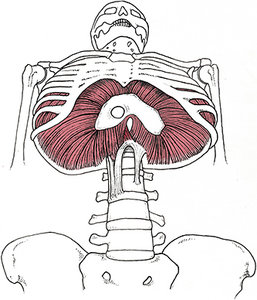

FIG 1 The diaphragm fires concentrically to create a negative pressure and draw air into the lungs, and eccentrically during exhalation to prevent the lungs from collapsing.13

Several studies have shown that weakness of the muscles of respiration correlate with poor outcomes following mechanical ventilation.7-8 One study showed that diaphragm weakness (Fig. 1) was present in 63 percent of patients reporting poor outcomes when placed on mechanical ventilators.8

FIG 1 The diaphragm fires concentrically to create a negative pressure and draw air into the lungs, and eccentrically during exhalation to prevent the lungs from collapsing.13

Several studies have shown that weakness of the muscles of respiration correlate with poor outcomes following mechanical ventilation.7-8 One study showed that diaphragm weakness (Fig. 1) was present in 63 percent of patients reporting poor outcomes when placed on mechanical ventilators.8

A Solution? Strengthening the Muscles of Inspiration

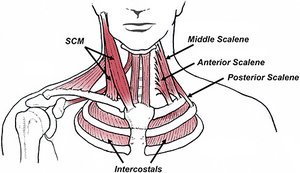

In an attempt to understand the best possible ways to improve outcomes in patients requiring mechanical ventilation, researchers from Toronto suggest success with mechanical ventilation requires more than a strong diaphragm.9 They cite several papers showing patients with partially and/or completely paralyzed diaphragms can still be weaned off ventilators as they become dependent upon secondary muscles of inspiration: notably, the scalenes, intercostals and sternocleidomastoid muscles. (Fig. 2)

FIG 2 The anterior, middle and posterior scalenes, along with the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and intercostal muscles, assist the diaphragm during inhalation.

The Canadian researchers performed a simple experiment in which they placed EMG sensors over the secondary muscles of inspiration and compared maximum inspiratory pressure as subjects performed either exercises to strengthen their neck flexors, or inspiratory muscle training to strengthen their diaphragm.

FIG 2 The anterior, middle and posterior scalenes, along with the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and intercostal muscles, assist the diaphragm during inhalation.

The Canadian researchers performed a simple experiment in which they placed EMG sensors over the secondary muscles of inspiration and compared maximum inspiratory pressure as subjects performed either exercises to strengthen their neck flexors, or inspiratory muscle training to strengthen their diaphragm.

The neck flexor exercises consisted of a series of quasi-isometric neck flexion exercises, in which subjects pressed their foreheads into a customized holder, generating 50 percent full effort for two seconds. This contraction was then followed by a four-second rest and repeated until the subjects were fatigued, which took a little over 25 minutes.

The group performing inspiratory muscle training also exercised at 50 percent full effort until fatigued, and the average duration of inspiratory muscle training was 38 minutes. The long exercise durations were specifically chosen in an attempt to increase endurance in these muscles, since it typically takes nearly an hour to wean the patient off of a ventilator.9

After analyzing their data, the authors noted that the neck exercises were easier to perform and produced significant increases in neck flexor strength, particularly in the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Interestingly, the sternocleidomastoid was also vigorously recruited during inspiratory muscle training. The authors were not surprised by this finding, as the sternocleidomastoid has the longest lever arm for increasing upward excursion of the ribs, making it a powerful synergist to the diaphragm.

Because neck flexor exercises are easy to perform and increase strength in the secondary muscles of respiration, they play a key role in respiration and can help offload an overworked and/or weakened diaphragm. The authors state: "Although addressing diaphragm weakness is of primary importance to facilitate weaning, improving the function of the neck and chest wall muscles will likely contribute to successful recovery following mechanical ventilation."

Given the difficult times ahead, it seems logical that in addition to improving immune function with an anti-inflammatory diet, vitamin D supplements, and mild to moderate exercise (all of which have been proven to reduce the risk of viral infection),10-12 everyone, especially high-risk individuals, should consider performing diaphragm and neck flexor exercises.

These exercises are easy to do and can be done at home with inexpensive equipment. (A diaphragm strengthening device called Expand-A-Lung is available for less than $30.) I typically recommend patients perform two sets of 30 repetitions at 70 percent full effort. To strengthen the neck flexors, I have patients perform four sets of 25 repetitions of partial sit-ups with the neck in a neutral position and the chin pointing up slightly. Once the head is elevated a few inches from the floor, I have them hold this position isometrically for 5 seconds.

Unlike deep neck flexor strength training, pointing the chin up slightly recruits the sternocleidomastoid muscle more effectively. This routine can be repeated twice a day and the number of repetitions can vary depending upon the person's fitness level. Within just a few weeks, you'll get appreciable strength gains in both the diaphragm and neck flexor muscles.

With any luck, by keeping our immune systems strong and our respiratory muscles functioning at maximum capacity, fewer people will require hospitalization once exposed to this difficult-to-treat virus.

References

- Coburn BJ1, Wagner BG, Blower S. Modeling influenza epidemics and pandemics: insights into the future of swine flu (H1N1). BMC Med, 2009 Jun 22;7:30.

- WHO Int. 2019 (Covid-19) Situation Report – 46, from the World Health Organization website.

- The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19): China, 2020 [J]. China CDC Weekly, 2020;2(8):113-122.

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med, 2020 (epub ahead of print).

- Beduneau G, Pham T, Schortgen F, et al. Epidemiology of weaning outcome according to a new definition: The WIND study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2017;195(6):772-783.

- Herridge MS, Chu LM, Matte A, et al. The RECOVER program: disability risk groups and 1-year outcome after 7 or more days of mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2016;194(7):831-844.

- Dres M, Dube BP, Mayaux J, et al. Coexistence and impact of limb muscle and diaphragm weakness at time of liberation from mechanical ventilation in medical intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2017;195:57-66.

- Dres M, Goligher EC, Dubé BP, et al. Diaphragm function and weaning from mechanical ventilation?: an ultrasound and phrenic nerve stimulation clinical study. Ann Intensive Care, 2018;8(53).

- Derbakova A, Khu S, Lewis C, et al. Neck and inspiratory muscle recruitment during inspiratory loading and neck flexion. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2020; Jan. 16 (online first).

- Martineau A, Jolliffe D, Hooper D, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ, 2017;356:16583.

- Gibson A, Neville E, Gilchrist S, et al. Effect of fruit and vegetable consumption on immune function in older people: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr, 2012 Dec;96(6):1429-36.

- Barrett B, Hayney M, Muller D, et al. Meditation or exercise for preventing acute respiratory infection: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med, July/Aug 2012;10(4):337-346.

Click here for more information about Thomas Michaud, DC.