| Figure 1: Charter of the National Chiropractic Insurance Company, dated 27 December 1945. |

The NCA and its organizational predecessors had a long tradition of providing legal services to chiropractors (Keating, 2000a). Indeed, the primary purpose for the 1906 formation of the UCA by B.J. Palmer and others had been to protect chiropractors against mounting prosecutions for unlicensed practice.

In 1931 it was estimated that DCs had collectively experienced some 15,000 prosecutions during the previous three decades (Turner, 1931). By this time, however, chiropractors had been successful in securing licensing legislation in more than half of the American states, and civil suits (especially involving malpractice) were replacing the previous volume of criminal cases. Nonetheless, legal defense services (civil and criminal, including the costs of attorney's services, settlements and judgments against defendant chiropractors) consumed a significant portion of the NCA's budget (see Table 1), which derived almost exclusively from members' dues.

| Table 1: Cash receipts and legal claims paid by the National Chiropractic Association, 1933-1945 (National, 1951). |

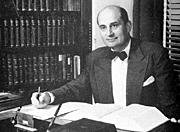

| Figure 3: Dr. George Hariman, from the November 1949 issue of the Journal of the NCA. |

The leadership of the NCA in 1945 included several individuals who are still remembered with affection today. Earnest Thompson,DC, a pioneer in chiropractic radiology, was president of the society, and Floyd Cregger,DC, faithful alumnus and later chairman of the board of regents of the Los Angeles College of Chiropractic (LACC), was NCA's vice president. Comprising the NCA's Board of Directors were the five DCs who would constitute the NCIC's first governing body (see Table 2): F. Lorne Wheaton of New Haven, Connecticut; Cecil Strait of Marietta, Georgia; George Hariman of Grand Forks, North Dakota (Keating, 2000c); Gordon Goodfellow, a 1925 alumnus of the LACC, former president (1936-37) of the NCA and leader in its educational reform movement (Keating et al., 1998); and Frank Logic of Iron Mountain, Michigan.

| Table 2: Officers and members of the original Board of Directors of the National Chiropractic Insurance Company, 1945-46 |

| Figure 6: This cartoon characterization of Frank O. Logic,DC of Iron Mountain, Michigan, a veteran of World War I, member of the NCA Board of Directors, and member of Michigan's Board of Chiropractic Examiners, appeared in the January 1942 issue of the National Chiropractic Journal |

The driving force behind the formation of the NCIC was NCA's longtime secretary-treasurer, Loran Rogers,DC, (Keating, 2000a), and the society's associate legal counsel, Robert Johns Sr. (Keating, 2000b). The NCA's legal protective services had come to the attention of Charles Fisher, Iowa Commissioner of Insurance, who insisted that these activities amounted to an insurance plan. The NCA was informed that it must either cease and desist or "convert what was a chiropractic mutual defense fund" into a properly organized insurance company under state regulation (Flaherty, 1997; Johns 1999).

| Figure 7: Relaxing, circa 1950, presumably during an NCA meeting, are (left to right): Loran M. Rogers,DC, Robert D. Johns, Sr.,JD and F. Lorne Wheaton,DC (photo courtesy of Sally Rogers Simonetti). |

Although the national society had at one point contemplated "lining up with an insurance firm" to provide malpractice coverage for its members (Gardner, 1945), Congressional reforms in insurance laws, which allowed for state rather than federal control of interstate insurance activity (Lorenz, 1995, pp. 1-2), may have persuaded the NCA to retain control of this area of service to its members. The association undoubtedly wished to retain the profits that its legal protective services garnered.

Meeting at the association's headquarters in Webster City, Iowa on 1-2 December 1945, the NCA Board of Directors authorized Rogers and Johns to incorporate "the National Chiropractic Insurance Company (or the Chiropractic Insurance Company of America)" (Minutes, 1945). The corporate charter was soon endorsed by Commissioner Fisher, who granted a "certificate of authority" to operate as a mutual insurer on 1 February 1946 (Rogers, 1965). The purposes of the NCIC were spelled out in the charter (at right).

The NCIC's start-up capital of $30,000 was provided by a loan from the NCA. Although the company did not involve itself in disability insurance as its charter permitted, it soon began issuing malpractice policies. Policy limits were $5,000 for unfavorable judgment against any single claim against a defendant chiropractor (plus attorneys' fees and court costs), and a maximum of $15,000 in any policy year. Policyholders paid $40 annually in premiums, and were billed for quarterly installments. The NCIC provided coverage exclusively to members of the NCA. Now, instead of legal protective services as a benefit of NCA membership, NCA membership became a requirement to buy NCIC malpractice insurance. This stipulation was dropped in later years for fear it would provoke anti-trust lawsuits.

| ARTICLE II The general nature of its business shall be:

|

The NCIC was incorporated as a mutual insurer. No shares are issued, but each policyholder is an owner of the company, and entitled to vote to elect the board of directors. (For convenience, the annual meeting of the NCIC's policyholders was held in conjunction with the NCA's annual convention.) Ordinarily in a mutual insurance corporation, policyholders can expect to receive dividends when company revenues exceed operating expenses. However, NCIC policyholders were required to waive all rights to any dividends from the company. The company's founders intended that profits be directed to worthy professional purposes, such as support of education and research through donations made to the Chiropractic Research Foundation (CRF). In its first two years of operation NCIC contributed $10,000 to the CRF (Answers, 1962), and would eventually become one of the largest financial supporters of chiropractic causes.

| Figure 8: This advertisement from the National Chiropractic Journal appeared throughout 1948. |

Unfortunately, the waiver-of-dividends stipulation would backfire in later years, when the U.S. Internal Revenue Service revoked the NCIC's tax advantage as a mutual corporation on the grounds that the waiver destroyed the "mutuality" of the corporate structure. The company challenged this ruling in federal court in 1970, but lost after a three-year legal battle (Forney, 1999). The problem was resolved by eliminating the waiver; the board still retained the prerogative to issue dividends or not, and to make grants for chiropractic causes as it saw fit. Recognition of the Council on Chiropractic Education by the U.S. Office of Education, which had been one of the chief goals of the profession's educational reform efforts, was accomplished shortly thereafter (1974); the malpractice insurer had been a major benefactor in this campaign.

| Figure 9: Dr. Loran M. Rogers, circa 1945 |

The NCIC grew slowly but steadily, its profitability augmented by its low-cost marketing strategy. No agents or brokers were employed; instead, NCA state delegates were encouraged to steer NCA members in their jurisdictions to the NCIC. Board members were not compensated (they were reimbursed for travel expenses), but treasurer L.M. Rogers,DC, received a modest salary for his duties as manager of the NCIC's "home office." Advertising was limited to the NCA Journal in the early years; NCA-NCIC secretary-treasurer Rogers was also editor of the Journal of the NCA. The company invested almost exclusively in low-yield federal savings bonds for many years; this conservative policy reflected NCIC's general aversion to risk. From its borrowed start-up capital of $30,000, the insurer's total assets grew to $650,000 in its first dozen years of operations, and the company's surplus (i.e., excess capital over reserves for claims filed) reached $405,998 (Minutes, 1958b). During this time the number of policyholders grew from 2,353 in 1946 to 4,324 by 1958. With much prodding from within, including a strong plea in 1951 from Montana delegate to the NCA, C.O. Watkins,DC, malpractice coverage was gradually expanded from the initial $5K/15K limits to $10K/30K in 1952, $15K/45K in 1955 and $20K/60K by 1957. Nearly a third of NCIC's initial clientele (1946) were California members of the NCA, and the company retained attorney C.P. Von Herzen, then counsel to the California Chiropractic Association and the LACC, to represent policyholders in the Golden State.

| Figure 10: Attorney C.P. von Herzen, circa 1950 |

The risks for the small, specialty malpractice insurer were real. Writing policies throughout the United States and in some Canadian provinces, NCIC was vulnerable from many sources. Although the number of claims and magnitude of judgments against policyholders were modest at first, they grew steadily over the years. The NCIC's legal department in Wisconsin warned early on that:

"...about 75% of all claims are the result of diathermy burns. The largest losses are cases involving arm and leg fractures, claimed fractures of vertebrae, and colonic irrigations....He stressed the importance of sending all information pertaining to the case to the La Crosse office immediately upon notice of a threatened suit, and warned the policyholders to make no statements admitting guilt in any pending case." (Minutes, 1948c.)

| Figure 11: Dr. James F. McGinnis, circa 1940 |

Scope of practice was a thorny problem from the beginning. Chiropractors in Oregon pressed for coverage of obstetrical and minor surgical practices as allowed by their statute, and were hesitantly accommodated by a special rider on their policies. When James McGinnis,DC,ND, of California applied for coverage, he was advised that a policy could only be written if he would cease referring to the manipulative methods he taught and practiced (Keating, 1998) as "bloodless surgery" (Minutes, 1947b). In its first decade of operations the NCIC Board of Directors had to review the risks and merits of insuring chiropractors for a variety of clinical procedures beyond the adjustive arts: among these were setting of fractures, colonic irrigation and proctology; "plasmatic therapy"; hypnosis; and physiotherapeutic modalities including ultrasound and diathermy. The company was also initially reluctant to insure chiropractic hospitals and interns in the college training clinics (Minutes, 1953a). Predictably, there would be dissatisfaction in the ranks. Nonetheless, it was clear that NCIC was run by and for chiropractors.

| Figure 12: Logo of the National Chiropractic Mutual Insurance Company. |

The National Chiropractic Mutual Insurance Company is now in its 56th year of operations, and has become the financially strongest institution in the profession. From humble beginnings it has weathered a myriad of storms and challenges, guided by its commitment to professional goals. The company's corporate structure has been an important factor in keeping it focused on its primary mission: protection of chiropractors. This is a success story by any measure, and merits further scrutiny.

References

- Answers of National Chiropractic Insurance Company to interrogatories of plaintiff (No. 122,533), Triton Insurance vs. Committee on Chiropractic Welfare, NCIC, et al., January 1962 (NCMIC Archives).

- Flaherty, Daniel. Letter to Louis Sportelli,DC, 5 December 1997 (NCMIC archives).

- Forney, Kent. Email message to J.C. Keating, 12 July 1999.

- Gardner, Edward. A written report on the NCA activities as given by E.H. Gardner before the executive board of the CCA, Saturday, 30 September 1945 (unpublished).

- Johns, Robert Sr. Telephone interview with Daniel Flaherty and J.C. Keating, 31 August 1999.

- Keating JC. James McGinnis,DC,ND,CP. Spinographer, educator, marketer and bloodless surgeon. Chiropractic History 1998 (Dec); 18(2): 63-79.

- Keating JC. Roots of the NCMIC: Loran Rogers and the National Chiropractic Association, 1930-1946. Chiropractic History 2000a (June); 20(1): 39-55.

- Keating JC. A founder and defender passes: Robert Johns, Sr.,JD. (1912-1999). Dynamic Chiropractic 2000b (Aug 6); 18(17): 38-41, 45.

- Keating JC. George Hariman,DC, profession builder. Dynamic Chiropractic 2000c (Oct 31); 18(23): 34-7.

- Keating JC, Rehm WS. The origins and early history of the National Chiropractic Association. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 1993 (Mar); 37(1): 27-51.

- Keating JC, Green BN, Johnson CD. "Research" and "science" in the first half of the chiropractic century. Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics 1995 (July/Aug); 18(6): 357-78.

- Keating JC, Callender AK, Cleveland CS. A history of chiropractic education in North America: report to the Council on Chiropractic Education. Davenport IA: Association for the History of Chiropractic, 1998.

- Lorenz, Charles J. Fifty Years of Independents: the Story of an American Insurance Revolution. Des Plaines, IL: National Association of Independent Insurers, 1995.

- Minutes of the meeting of the board of directors of the Proposed National Chiropractic Insurance Company, 1-2 December 1945 (NCMIC archives).

- Minutes of annual meeting of board of directors of the National Chiropractic Insurance Company, Hotel Fontenelle, Omaha, 9 August 1947b (NCMIC Archives).

- Minutes of mid-year meeting of board of directors of the National Chiropractic Insurance Company, Inc., Hotel Sherman, Chicago, 16 January 1953a (NCMIC archives).

- Minutes of annual meeting of the board of directors of the National Chiropractic Insurance Company, Fontainbleau Hotel, Miami Beach, 22 June 1958b (NCMIC archives).

- National Chiropractic Association, Inc. v. Birmingham et al., Civ. A. No. 608, United States District Court for the Northern District of Iowa, Western Division, 96F. Supp. 874; 1951 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 2538; 40 A.F.T.R. (P-H) 536; 10 April 1951.

- Rogers, Loran M. Are you adequately protected in your practice? ACA Journal of Chiropractic 1965 (Dec); 2(12): 25, 46, 48.

- Turner, Chittenden. The Rise of Chiropractic. Los Angeles: Powell Publishing Company, 1931.

Joseph Keating Jr., PhD

Phoenix, Arizona

Click here for previous articles by Joseph Keating Jr., PhD.