Chiropractic - the profession - has almost always been a multiheaded creature. Raised in an environment that saw 15,000 prosecutions through 1930 (Turner, 1931, p. 294), DCs adopted whatever "legal clothing" (John Howard,DC, quoted in Beideman, 1983) they could to avoid the sting of political medicine's wrath. Chiropractic in the courtroom became "nontherapeutic" and "nondiagnostic," so as to be construed as "nonmedical."

Analysis replaced diagnosis, and "adjusting the cause" supplanted treatment of "dis-ease." Some sought exemptions from the law, as with the "Wisconsin Idea," wherein the doctor could practice legally, so long as he or she hung a sign indicating the lack of licensure. Others sought refuge in the religious exemption clauses of various state medical practice acts (Palmer, 1914). Still, others sought "separate and distinct" licensing laws, and boards of chiropractic examiners (BCEs) as an alternative to allopathic hegemony (Wardwell, 1992b).

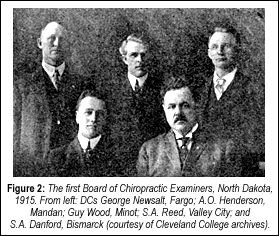

Efforts to establish licensure were opposed by political medicine and elements within the profession (Budden, 1935; Gibbons, 1993). Kansas broke the ice with the first chiropractic statute in 1913, and North Dakota awarded the first license from a BCE in 1915. The public rallied to the profession's unified call for "health freedom" and the right of patients to choose their own healers. However, as licensure spread from state to state, rapidly at first, a wide range of defining clauses and differing scopes of practice were carved into legal stone. Chiropractors organized competing state and national associations, each pressing for its own vision of the chiropractic art. They fought with one another,and sometimes convinced legislators that each was not prepared to assume the responsibilities of an organized professional body. Although some 37 American states and territories had passed chiropractic statutes by 1930 (Wardwell, 1992a, pp. 110-1), it required another 44 years for the final 14 jurisdictions to do so. Similarly, chiropractors' continuing pleas for recognition in the armed forces during both World Wars went largely unheard (e.g., Keating, 1994), a victim of the profession's lack of unity and credibility as well as organized medicine's assault.

With the rapid loss of its legal monopoly, encroached upon first by the osteopaths, and next by the chiropractors and naturopaths, organized allopathy sought new measures to block the "quacks." Chiropractors threatened not merely medicine's economic turf, but perhaps more importantly, its self-assumed authority as the final arbiter in all matters of health care. The allopaths would strike where they believed chiropractors to be weakest: the educational system (Brennan, 1983).

Basic science legislation was first introduced in Connecticut and Wisconsin in 1925, and devastated the chiropractic ranks for decades (Gevitz, 1988). Chiropractors were frequently unable to defeat the logic behind political medicine's seemingly sensible requirement that all healers first pass examinations in the fundamental life sciences, common to all schools or sects of healing. These included tests in anatomy; physiology; pathology; bacteriology; chemistry; hygiene; and sometimes diagnosis or public health, and had to be passed before taking licensing exams from medical, osteopathic or chiropractic boards. John Nugent,DC, a 1922 Palmer graduate who had clashed with B.J. as a student, wrote the language of Connecticut's basic science law. He provoked the enmity of chiropractors for decades to come, both for this and for his role as NCA Director of Education (1941-1961). B.J. Palmer referred to him as the "Antichrist" of chiropractic. Eventually, 24 American jurisdictions passed basic science legislation, and the last of these statutes was not repealed until 1979.

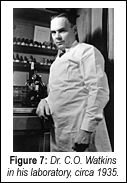

Some leaders saw purification of the chiropractic ranks as the only solution to the spread of basic science legislation. B.J. Palmer blamed the new scourge upon "mixer" chiropractors' encroachment upon the medical scope of practice, and predicted doom for the profession (Caster, 1928). Others saw grassroots political action, the same strategy that had produced chiropractic legislation, as the only viable solution. At least one BCE simply ignored the basic science law in state, and licensed chiropractors without the basic science certificate (Gevitz, 1988), at least until the state's attorney general caught up with them. Led by William Schulze,MD,DC, and William Budden,DC,ND, the National College of Chiropractic offered yet another route to challenging the basic science barrier: "(1) study basic science; (2) study basic science; (3) study basic science; and (4) study basic science" (National, 1928). Leaders of the National Chiropractic Association (NCA), such as C.O. Watkin,DC. (Keating, 1987), who had earlier referred to the "damnatory basic science laws" (Watkins, 1934), gradually grew appreciative of the impetus that basic science laws lent to the NCA's efforts to upgrade chiropractic education.

Joseph Keating Jr., PhD

Phoenix, Arizona

References

- Beideman RP. Seeking the rational alternative: the National College of Chiropractic from 1906 to 1982. Chiropractic History 1983;3:16-22.

- Brennan MJ. Perspective on chiropractic education in medical literature, 1910-1933. Chiropractic History 1983;3:20-30.

- Budden WA. Medical propaganda aided by B.J. Palmer defeats healing arts amendment. The Chiropractic Journal 1935 (Feb);4(2):9-10,38.

- Caster CE. "B.J. admits chiropractic is doomed." from the American Medical Journal, March 17, 1928. Hawkeye Chiropractor 1928 (Apr);3(5):1,5.

- Gevitz N. "A coarse sieve": basic science boards and medical licensure in the United States. Journal of the History of Medicine & Allied Sciences 1988;43:36-63.

- Gibbons RW. Minnesota, 1905: Who killed the first chiropractic legislation? Chiropractic History 1993 (June);13(1):26-32.

- Gitelman R. The history of chiropractic research and the challenge of today. Journal of the Australian Chiropractors' Association 1984 (Dec);14(4):142-6.

- Grod J, Sikorski D, Keating JC. The unsubstantiated claims of the largest state, provincial and national chiropractic associations and research agencies. Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics 2001 (Oct); 24(8):514-9.

- Keating JC. C.O. Watkins: pioneer advocate for clinical scientific chiropractic. Chiropractic History 1987 (Dec); 7(2):10-5.

- Keating JC. The influence of World War I upon the chiropractic profession. Journal of Chiropractic Humanities 1994;4:36-55.

- Keating JC. Chiropractic: Science and antiscience and pseudoscience, side by side. Skeptical Inquirer 1997 (July/Aug);21(4):37-43.

- Keating JC, Green BN, Johnson CD. "Research" and "science" in the first half of the chiropractic century. Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics 1995 (July/Aug); 18(6):357-78.

- Keating JC, Caldwell S, Nguyen H, Saljooghi S, Smith B. A descriptive analysis of the Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics, 1989-1996. Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics 1998a (Oct);21(8):539-52.

- Keating JC, Callender AK, Cleveland CS. A History of Chiropractic Education in North America: Report to the Council on Chiropractic Education. Davenport IA: Association for the History of Chiropractic, 1998b

- Miller JL. From the president. Palmer/West Magazine 1984 (Sum);2(1):2-3.

- National (College) Journal of Chiropractic 1928 (Dec);5(14):12.

- Palmer DD. The Chiropractor's Adjuster: The Science, Art and Philosophy of Chiropractic. Portland, OR: Portland Printing House, 1910.

- Palmer DD. The Chiropractor. Los Angeles: Beacon Light Printing Company, 1914.

- Stephenson RW. Chiropractic Text Book. Davenport IA: Palmer School of Chiropractic, 1927.

- Strauss JB. Refined by Fire: The Evolution of Straight Chiropractic. Levittown PA: Foundation for the Advancement of Chiropractic Education, 1994.

- Turner Chittenden. The Rise of Chiropractic. Los Angeles: Powell Publishing, 1931.

- Wardwell WI. Chiropractic. History and Evolution of a New Profession. St. Louis, Mosby, 1992a.

- Wardwell, Walter I. Chiropractors' struggle for legal recognition: balancing rights and protections. Chiropractic History 1992b (Dec);12(2):25-31.

- Watkins CO. The new offensive will bring sound professional advancement. The Chiropractic Journal (NCA) 1934 (June);3(6):5,6,33.

- Watkins CO. The basic principles of chiropractic government. Sidney MT: the author, 1944; reprinted as Appendix A in: Keating JC. Toward a Philosophy of the Science of Chiropractic: A Primer for Clinicians. Stockton, CA: Stockton Foundation for Chiropractic Research, 1992.

Click here for previous articles by Joseph Keating Jr., PhD.