We'll finish our tour of the spine and dura with the most caudal segment, the coccyx, which is key for a number of reasons: It is often injured, especially in falls on the buttock, and it's the last attachment of the dura mater and the filum terminale.

When the coccyx is under stress, whether from a fall or an accumulation of factors, it usually seems to be stuck primarily forward. (An exception to this is a posterior coccyx, post-pregnancy.) The anterior positioning is rather inconvenient for the chiropractor, as this makes it more difficult to access. It can simultaneously be pulled to the right or the left, which will reflect itself in increased tension on the sacrotuberous ligament. The coccyx can also be jammed superiorly, creating a compression at the sacrococcygeal joint.

I could give multiple case histories of patients I have helped by correcting the coccyx, but they basically fall into two categories: patients who fell on their tailbones and have suffered with coccygeal pain since, sometimes for weeks, sometimes for years; and patients with lower back pain who are not responsive to my work on their sacroiliac, discs, lumbar segments or muscles. Correcting a subluxed coccyx often makes a dramatic difference in patients' spinal patterns, helping symptoms and allowing self-stabilization and self-correction.

Assessment of the Coccyx

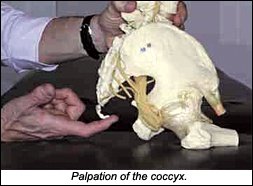

How can we assess the tailbone? You will miss most coccygeal problems if you strictly palpate down to the sacrococcygeal junction. You need to reach the tip of the coccyx. The best method I know is to have the patient sitting, with the doctor behind and to the side. The patient must loosen his or her trousers; you palpate between the trousers and underwear. Thong underwear makes the area impossible to feel, so reach under them (wearing a glove) and under the tailbone, with the patient leaning forward. As he or she leans forward, slide your index or middle finger further forward until you reach the anterior tip of the tailbone, then have the patient sit upright slowly, which will bring the tip of the tailbone down onto your hand. If the inferior tip of the coccyx doesn't come into your hand, pull gently posterior and superior with your finger to find this structure. You'll notice that most men have a short, stubby coccyx, while most women have a longer coccyx that goes further anterior. Sometimes, it is difficult to reach the most anterior part of the coccyx with your finger. Note that the coccyx has multiple segments, but we treat it as if it were one single bone.

Obviously, you need to tell the patient what you intend to do. The coccyx is a difficult and sensitive area to get to, being at the very bottom of the buttock. Be clear, explain with a model if you need to, and get clear permission for your palpation and correction.

You are looking for tenderness and restriction. When the tailbone is a problem, it is usually sharply tender. Test with gentle palpation for restriction in the anterior-posterior direction and assess the lateral-to-medial direction on both sides. Tenderness and restriction are usually found together.

External Coccyx Correction

How do we correct the coccyx? I'll outline external techniques first. Some procedures emphasize releasing the sacrococcygeal junction with a posterior-to-anterior adjustment, hoping that this will bring the coccyx itself further posterior. I have not found this particularly effective. I prefer to directly pull the tip of the coccyx further posterior, simultaneously addressing superior jamming and right or left lateral bending. To do this, I have to get to the front of the coccyx. This can usually be done with the patient in the sitting position, as outlined in the palpation method above, or in a prone or side-lying position.

With any patient position, I use one of two basic techniques. The main technique I use is "engage, listen, follow," or ELF. Engage the beginning of the barrier by bringing the coccyx posterior, left or right, and inferior, if needed. As the subluxation is never purely linear, we always fine-tune, so find the exact 3-D direction of the barrier. You'll feel the coccyx and the associated soft tissues soften and release over 10-60 seconds. If the area is not releasing, you are probably pressing too hard, going to the hard end of the barrier. You just need to back off a bit to allow the patient's body to begin the correction.

Another useful tool for a coccyx that is not releasing easily is postisometric contraction. Having the patient hold a very gentle pelvic floor contraction after you have engaged the coccyx to its initial barrier can help the whole area release. Repeat three to five times, having the patient maintain the gentle contraction for three to five seconds. In the relaxation phase, you are taking the coccyx further into the receding barrier. A recoil adjustment also enhances the release when the area feels stuck. In recoil ("engage-release"), you engage the barrier, then suddenly release your pressure. This can be made more effective by using respiration, either at the end of inspiration or at the point in the respiratory cycle where the tension suddenly builds. Note that this is quite different than toggle-recoil.

Internal Coccyx Correction

I always start with some variation on the above external techniques. If they are successful and the tenderness and restriction does not recur - great! If the area remains tender after one or two treatments, I may suggest an internal correction to the patient, explaining this in some detail. I mention that I will be using a lubricated gloved finger to contact the coccyx through the rectum. I tell the patient that it is uncomfortable, but not usually painful. I tell him or her that I will have an assistant in the room.

Trying to explain this technique solely in print is not ideal. Practice with a colleague or spouse until you are comfortable with the basic procedure. Next, perform it, when clinically indicated, on a patient with whom you have a good trusting relationship. You really don't want to be fumbling around with a new patient in this sensitive area. This procedure may not be legal in some states, and I recognize that doing an internal coccygeal correction may carry increased liability risk. However, I am also very clear that my duty as a chiropractor is to correct whatever structures need manual correction in the whole neuromusculoskeletal axis, and if this requires me to work internally on the tailbone, I will. You want to project perfect clarity, confidence, and to have clearly explained the procedure to the patient, and obtained his or her clear consent. Document that you had a PARQ ("procedures, alternative, risks, questions") conference with the patient. A signed written consent form is ideal.

Many of your patients will have experienced physical or sexual abuse as children, and may have issues with touch to sensitive areas. I try to be aware of this, and when I ask permission to work on a sensitive area, I am attempting to assess the patient's response. I want the patient to maintain eye contact with me, and give me a clear "yes"- a clear permission to proceed. If the patient dissociates in any manner, by closing his or her eyes, looking away, or not stating clear permission, I am very hesitant to proceed.

How do we perform the internal correction? We start with having the patient draped and lying on either the side or prone with a pillow under the belly. To initiate the entrance into the rectum, one must be aware that there are two anal sphincters. Ask the patient to contract the anus, and as he or she does, apply a slight pressure to the external anal sphincter (EAS), then ask the patient to relax. As the patient relaxes, enter the EAS with a well-lubricated, gloved finger. Repeat the contract and relax several times to get past both sphincters (the internal is softer and wider). Another way to do this is with the patient side-lying. Enter the rectum with the patient having pulled the legs up into a fetal position, then straightening the legs for the correction.

Once I find the coccyx, I palpate, and ask the patient where the coccyx is tender. I note the tender places, and begin my low-force ELF manipulation. I can use my other methods, including recoil and postisometric relaxation, in concert with the ELF. I can also use the other hand or the thumb of my active hand on the external surface. I engage the coccyx externally while the internal finger listens and assists. I have the coccyx sandwiched between my two contacts, which improves my palpatory sense. This enhances the correction, especially if I need to pull the coccyx inferiorly to correct superior compression. I always keep both contacts gentle. I need only mild pressure to make the correction.

Once I've corrected the basic restriction of the coccyx in the A-P and lateral-to-medial directions, I can assess and correct two other potential lesions. The first type is a tender spot anywhere on the anterior surface of the coccyx or sacrum, wherever I can reach. If I find a tender spot, which will feel stiffer, I again use ELF, more as a myofascial release, to release the tension in the fascia on the anterior surface of the sacrum. The second possible correction is for myofascial tensions at the origin of the piriformis. The piriformis originates from the lower anterior surface of the lateral aspect of the sacrum. It is usually within reach. I find the tender spots within this, and use ELF as a myofascial release. I only want to make this invasive correction once, so I try to correct every dysfunction I find on the anterior surface of the coccyx and sacrum.

Once I've completed the corrective procedures, I reassess for tenderness. I remove my finger slowly, asking the patient to contract the pelvic floor again. (This prevents the patient from feeling as if he or she is having a bowel movement.)

The whole internal procedure takes me between one minute and four minutes. I always make this the last major procedure I do on the patient during the office visit. I may finish with a balancing of the sacrum's craniosacral motion, following its inherent motion. This calms the nervous system and integrates the sacrum and coccyx with the whole of the spine.

This internal coccygeal correction is one of the most powerful and effective procedures in my toolbox, and I use it with respect. I almost never have to repeat it; the coccyx almost always stays corrected, unless there is a new trauma.

Resources

- Special thanks to Surya Bolom, DC, Mark Thomas, DC, and Ramona Horton, PT, for feedback on this article.

- Barral JP. Visceral Manipulation. 1989, Eastland Press.

- Barral JP. Urogenital Manipulation. 1993, Eastland Press.

- Urogenital manipulation course, October 2000, St. Etienne, France, taught by Jean Pierre Barral.

Click here for more information about Marc Heller, DC.