It is well-known that metabolic changes in children, including insulin resistance, may be responsible for accelerated biological maturation, manifested as accelerated bone age. This may lead to hypertension and cardiovascular disease in the future.

This was a cross-sectional control study of children diagnosed with PH vs. normotensive control subjects to examine the prevalence of advanced bone age (BA) and its role in predicting PH in children and adolescents. The study utilized dual X-ray absoptiometry-derived hand scans of 54 newly diagnosed children and adolescents with PH and 54 healthy controls matched for body mass index, age and sex. Chronological age (CA), body height, body weight, BMI and blood pressure were assessed. Results were as follows:

Ossification Centers and Epiphyseal Growth-Plate Maturation of the Carpals, Including the DIPS and PIPs*

| Bone | Appearance | Closure |

| Capitate | 2 months | 13 to 15 years |

| Hamate | 3 to 4 months | 13 to 15 years |

| Radius | 10 to 12 months | 16 to 17 years |

| Triquetrum | 2 to 3 years | 13 to 15 years |

| Lunate | 3 years | 13 to 16 years |

| Scaphoid | 4 to 5 years | 13 to 16 years |

| Trapezium | 4 to 6 years | 13 to 16 years |

| Trapezoid | 4 to 6 years | 13 to 16 years |

| Ulna | 6 years | 15 to 17 years |

| *The basis of Greulich and Pyle's atlas for determining BA. | ||

The healthy controls had a mean BA of 14.7 years and a mean CA of 14.2 years. The PH group had a mean BA of 16.0 years and a mean CA of 14.1 years. The magnitude of acceleration of skeletal maturation (BA-CA) and its prevalence (88.9 percent) was significantly higher in the PH group, compared with BMI-matched controls (37 percent). It is known that BMI is a factor in accelerated BA, but regardless of BMI, the statistical results lead to the conclusion that advanced biological maturation should be considered an independent marker for the development of hypertension.

So, what does that have to do with chiropractic? Simply put, we need to be aware of accelerated BA in our pediatric patients. Helping patients avoid diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease should be a high priority in anyone's practice. The standard way of determining the skeletal age of a child is to use an X-ray of the left wrist and compare it with X-rays of the Greulich and Pyle atlas.2 Comparing your patient's X-ray with norms of the same age (now easily accomplished via a computerized program) yields the patient's BA.

I am not suggesting that all your pediatric patients need to have their BA assessed. However, if X-rays have been taken, consider looking for signs of accelerated BA, especially in overweight patients. Disorders that bring the pediatric patient into chiropractic offices are back pain or scoliosis. An AP lumbar film is often taken, depending on the history and symptoms. If an AP lumbar film is available no further X-rays are needed. Just use the Risser's sign to determine if accelerated BA is present. Further evaluation can then be performed to confirm the presence of accelerated BA.

One can also use a lateral cervical spine X-ray to determine growth and maturation using Lamparski's method.3 This method often assesses the morphological changes associated with growth and maturation of the cervical vertebrae in six stages; also very legitimate. Kamal, et al., reported a comparative study evaluating the hand/wrist and cervical vertebrae and demonstrating that cervical vertebrae can be used with the same confidence as hand/wrist radiographs to evaluate skeletal maturity.4

The Risser Sign: Grade and Average Age (Boys/Girls)

| Girls | Boys | ||

| Risser | Age | Risser | Age |

| 1 | 13.8 | 1 | 15.2 |

| 2 | 14.3 | 2 | 15.2 |

| 3 | 14.7 | 3 | 16.3 |

| 4 | 16.0 | 4 | 16.3 |

| 5 | 16.1 | 5 | 18 |

Fig. 2: Comparison of the Risser sign and maturation of the hand/wrist.

The Risser sign uses the appearance of the iliac apophysis to assess BA. The apophysis appears laterally along the iliac crest and moves toward the spine with the approach of skeletal maturation. Using the Risser's sign, one can measure the growth left in the spine. This method is generally used to help to determine the potential for progression of scoliosis, but can certainly be used for determining BA. Grading (based on iliac crest divided into four quadrants) involves the following:

Fig. 2: Comparison of the Risser sign and maturation of the hand/wrist.

The Risser sign uses the appearance of the iliac apophysis to assess BA. The apophysis appears laterally along the iliac crest and moves toward the spine with the approach of skeletal maturation. Using the Risser's sign, one can measure the growth left in the spine. This method is generally used to help to determine the potential for progression of scoliosis, but can certainly be used for determining BA. Grading (based on iliac crest divided into four quadrants) involves the following:

- Risser 1: 25 percent iliac apophysis ossification; anterior superior iliac spine (anterolateral). Seen in pre-puberty or early puberty.

- Risser 2: 50 percent iliac apophysis ossification. Ossification extends halfway across iliac wing. Seen immediately before or during growth spurt.

- Risser 3: 75 percent iliac apophysis ossification. Indicates slowing of growth.

- Risser 4: 100 percent ossification with no fusion to iliac crest. Indicates slowing of growth.

- Risser 5: Iliac apophysis fuses to iliac crest. Indicates cessation of growth.

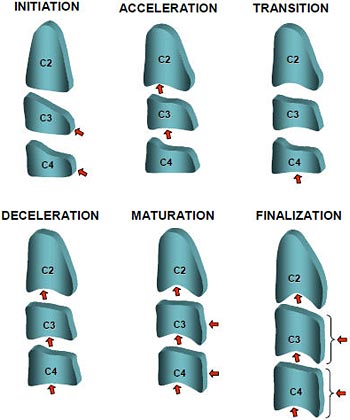

Fig. 3: Cervical spine maturation: cervical vertebrae maturation indicators (CVMI).

Lamparski's method established a maturational pattern for cervical vertebrae using vertebrae C2-C6, consisting of six stages.3 This method of evaluating skeletal maturation is now called the cervical vertebrae maturation indicators (CVMIs) and are as follows: initiation (stage I); development of concavities on the lower borders of the vertebral bodies (stage II); increase of the anterior portion and of the total height of these vertical bodies causing changes in their shape (stage III); changing from a wedge shape to a rectangular shape (stage IV), and later, to a square (stage V); and finally, presenting a predominance of height over width (stage VI).

Fig. 3: Cervical spine maturation: cervical vertebrae maturation indicators (CVMI).

Lamparski's method established a maturational pattern for cervical vertebrae using vertebrae C2-C6, consisting of six stages.3 This method of evaluating skeletal maturation is now called the cervical vertebrae maturation indicators (CVMIs) and are as follows: initiation (stage I); development of concavities on the lower borders of the vertebral bodies (stage II); increase of the anterior portion and of the total height of these vertical bodies causing changes in their shape (stage III); changing from a wedge shape to a rectangular shape (stage IV), and later, to a square (stage V); and finally, presenting a predominance of height over width (stage VI).

The vertebral maturity indicators are the same for males and females. The CVMI is considered to have the same clinical value as the hand-wrist evaluations. As in most maturation evaluations, each stage of vertebral development occurs earlier in females than in males.

Because of the rise in chronic diseases in children, we need to be more acutely aware of the signs associated with early onset of chronic disease. Accelerated bone maturation is one sign. Parents should be aware that skeletal and pubertal maturation is accelerated with obesity. Most researchers believe that skeletal maturation cannot be reversed, but nutrition and weight loss can slow the acceleration.

References

- Pludowski P, Litwin M, Niemirska A, et al. Accelarated [sic] skeletal maturation in children with primary hypertension. Hypertension, 2009 Dec;54(6):1234-9.

- Greulich WW, Pyle SI. Radiographic Atlas of Skeletal Development of the Hand and Wrist, 2nd Edition. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1959.

- Lamparski DG. "Skeletal Age Assessment Utilizing Cervical Vertebrae." Master's thesis, University of Pittsburgh, 1972.

- Kamal M, Ragini, Goyal S. Comparative evaluation of hand wrist radiographs with cervical vertebrae for skeletal maturation in 10-12 year old children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent, 2006;24:127-35.

Click here for more information about Deborah Pate, DC, DACBR.