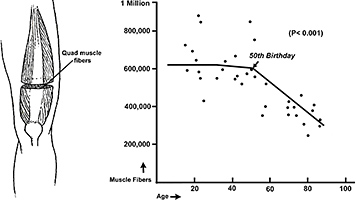

It's a depressing fact, but shortly after age 50, you begin to lose nearly 2 percent of your muscle fibers each year. Figure 1 is a graph of the average number of quadriceps muscle fibers present in adults ages 18 to 82.1 Looking at the center of the graph, you can see how the number of muscle fibers remain stable through your 30s and 40s.

Unfortunately, this reduction in muscle mass is associated with a threefold reduction in strength and power, which begins a downward spiral of frailty that correlates strongly with disability, falls and reduced lifespan.2 Several studies have shown that age-related muscle loss (also known as sarcopenia) is associated with the development of osteoarthritis, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, cognitive decline and even cancer.3-5

Exercise for Muscle Preservation: The Problem With Heavy Repetitions

While research confirms that regular exercise can reduce the speed of muscle wasting, there is a surprising amount of controversy regarding what type of exercise is best for maintaining muscle mass. According to the American College of Sports Medicine, the only way to effectively build muscle is to perform multiple sets of 8-12 repetitions using heavy weights.6

FIG 1 Total number of fibers present in the quadriceps muscles of men between the ages of 18 and 82 years.1

The theory is that heavy weights are needed to recruit the maximum number of muscle fibers in order to stimulate remodeling. The problem with using heavy weights is that as people age and muscle fibers begin to disappear, the vanishing muscle fibers are replaced with fat and scar tissue, which significantly weakens muscles and tendons.7 Age-related weakening of muscle fibers explains why seniors are 10 times more likely to be injured while lifting heavy weights compared to their younger peers.

FIG 1 Total number of fibers present in the quadriceps muscles of men between the ages of 18 and 82 years.1

The theory is that heavy weights are needed to recruit the maximum number of muscle fibers in order to stimulate remodeling. The problem with using heavy weights is that as people age and muscle fibers begin to disappear, the vanishing muscle fibers are replaced with fat and scar tissue, which significantly weakens muscles and tendons.7 Age-related weakening of muscle fibers explains why seniors are 10 times more likely to be injured while lifting heavy weights compared to their younger peers.

A Better Option: Light Resistance

Fortunately, a growing body of research shows it is possible to build muscle mass using light resistance exercise. In 2013,8 researchers compared changes in muscle volume in subjects who performed conventional high-resistance two-weight training (two sets of 10-15 reps performed at near full effort), with subjects who performed one set of 60 repetitions at 15 percent of full effort, followed immediately with one set of 12 repetitions performed at 40 percent full effort (i.e., the subjects were exhausted after the 60th and after the 12th repetition, respectively).

The researchers were surprised that the low-intensity routine produced the same gains in muscle volume as high-intensity weight training. They state that prior to their study, "virtually no studies have focused on the effects of such high-repetition protocols."

In 2018, researchers from Japan had 88 men and women ages 70 years or older participate in a weight-training program in which they performed two sets of 10-14 repetitions daily for 12 weeks.9 The subjects used body weight alone and performed the movements very slowly (four seconds up and four seconds down).

At the end of the 12-week training program, in addition to significant increases in muscle mass, participants also had decreased hip and waist circumference and reduced abdominal fat. This study is remarkable because the participants had no prior experience with weight training, the exercises were performed at home (taking less than 15 minutes each day), and at the end of the study, only two of the 88 people involved had dropped out.

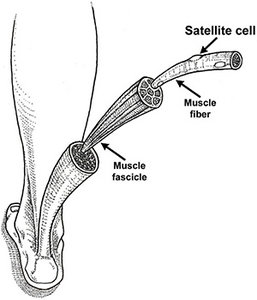

FIG 2 Satellite cells surround muscle fibers (especially fast-twitch muscle fibers) and are responsible for muscle repair. While satellite cells can't replace lost muscle fibers, they take the fibers you have and make them thicker and stronger, regardless of your age.

In a 2019 study,10 researchers measured muscle hypertrophy following a 10-week exercise routine in which subjects performed one set of exercises lifting either heavy weights (80 percent full effort), or light weights (30 percent full effort) until they were fatigued. (Usually, subjects lifting weights at 30 percent full effort fatigue after 20-25 repetitions.) Surprisingly, while both protocols increased muscle strength and volume, only the light weights resulted in a significant increase in the number of mitochondrial proteins associated with accelerated repair and remodeling. (Figure 2)

FIG 2 Satellite cells surround muscle fibers (especially fast-twitch muscle fibers) and are responsible for muscle repair. While satellite cells can't replace lost muscle fibers, they take the fibers you have and make them thicker and stronger, regardless of your age.

In a 2019 study,10 researchers measured muscle hypertrophy following a 10-week exercise routine in which subjects performed one set of exercises lifting either heavy weights (80 percent full effort), or light weights (30 percent full effort) until they were fatigued. (Usually, subjects lifting weights at 30 percent full effort fatigue after 20-25 repetitions.) Surprisingly, while both protocols increased muscle strength and volume, only the light weights resulted in a significant increase in the number of mitochondrial proteins associated with accelerated repair and remodeling. (Figure 2)

Although the exact mechanism is unclear, it is theorized that the higher number of repetitions produces a greater increase in intramuscular pressure, essentially squeezing blood out of the muscle. The reduced blood flow decreases oxygen levels, causing a shift in muscle recruitment from just a few slow-twitch muscle fibers (which are dependent upon oxygen) to a much larger number of fast-twitch muscle fibers (which can function in an oxygen-free environment).

The more fast-twitch muscle fibers recruited with each set, the more specialized cells called satellite cells work to stimulate remodeling. Apparently, long rests between sets allow for the restoration of blood flow, which restores circulation and allows the body to go back to using just a few slow-twitch muscle fibers.8

5 Exercises for Maintaining Muscle Mass: The Sarcopenia Workout

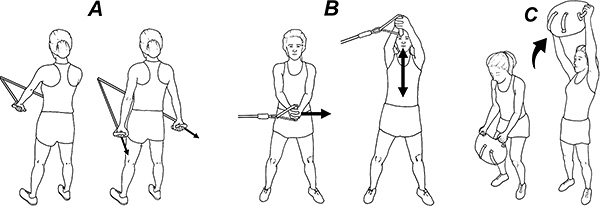

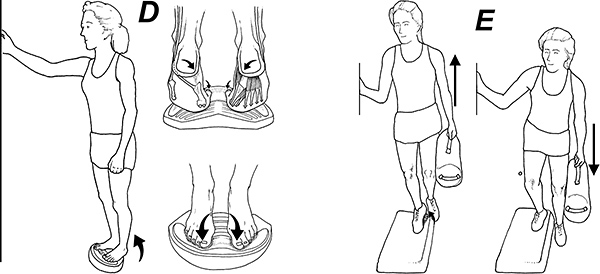

Figure 3 reviews five simple exercises to maintain muscle mass in nearly every muscle of the body. (A video of the exercises is available at HumanLocomotion.org.) This routine, which can be performed at home with minimal equipment, takes about 15 minutes to complete and should be repeated at least twice a week.

B: Oblique twist and lift. With the exercise band at waist level, step sideward until the band is on tension (horizontal arrow). Maintain tension as you raise and lower the band 25 times (vertical arrow). Face the opposite direction and repeat. This exercise targets the abdominal obliques, rhomboids and serratus anterior.

C: Partial forward lift. Hold a weighted sandbag or backpack just above the knees and use your knees, hips, shoulders and arms to lift the bag upward (arrow). The lumbar spine should be maintained in a neutral position and you should use enough weight to be fatigued after 25 repetitions. Repeat two times. This is an excellent functional exercise that targets the quads, glutes, low back, anterior deltoids, and biceps. If you have a history of shoulder injuries, don't lift the bag above your head.

E: Lateral step-ups with weighted bag. Using the same weight used in exercise C, place one foot on a 4- to 6-inch platform and do 25 repetitions stepping up onto the platform while holding onto a wall or stable surface. The stepping knee should not twist in and it should bend only a small amount. Bending the knee more than 45 degrees (as with squats) produces dangerous amounts of pressure on the back of the kneecap.13 Lateral step-ups have been shown to effectively target the inner quad and hip musculature, while placing very little strain on the knee itself. Performing a slight hip hinge while raising and lowering the weight allows you to isolate the hip rotators and abductors. Perform two sets of 25 repetitions on each leg.

Because the body adapts to specific exercise protocols, vary sets and repetitions on 12-week cycles. Some of the sets should be performed quickly and some slowly. The most important factor is to begin strength training early in life because it is not possible to increase the total number of muscle fibers in the body; it is only possible to maintain existing muscle fibers.

References

- Campbell MJ, McComas AJ, Petito F. Physiological changes in aging muscles. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 1973;36(2):174-82.

- Goodpaster B, et al. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J Gerontol, 2006;61:1059-1064.

- Kishimoto H, et al. Midlife and late-life handgrip strength and risk of cause-specific death in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama Study. J Epidemiol Community Health, 2014;68:663-8.

- Suwa M, et al. Age-related reduction and independent predictors of toe flexor strength in middle-aged men. J Foot Ankle Res, 2017;10:15.

- Mainous A, et al. Grip strength as a marker of hypertension and diabetes in healthy weight adults. Am J Prev Med, 2015;49:850-8.

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM'S Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Philadelphia,PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

- Vettor R, et al. The origin of intermuscular adipose tissue and its pathophysiological implications. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2009;297(5):E987-98.

- Van Roie E, et al. Impact of external resistance and maximal effort in force-velocity characteristics of the knee extensors during strengthening exercise: a randomized controlled experiment. J Strength Cond Res, 2013;27:1118-27.

- Tsuzuku S, et al. Slow movement resistance training using body weight improves muscle mass in the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 2018;28:1339-44.

- Lim C, et al. Resistance exercise-induced changes in muscle metabolism are load dependent. Med Sci Sports Exerc, July 11, 2019.

- Goldmann J, Maximilian Sanno, Steffen Willwacher, et al. The potential of toe flexor muscles to enhance performance. J Sports Sci, 2012;31:424-433.

- Mickle, K, et al. ISB Clinical Biomechanics Award 2009: Toe weakness and deformity increase the risk of falls in older people. Clin Biomech, 2009;24:787-791.

- Powers C, Ho K, Chen Y, et al. Patellofemoral joint stress during weight-bearing and nonweightbearing quadriceps exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2014;44:321-327.

Click here for more information about Thomas Michaud, DC.