In my previous article [June issue], I reviewed Mike O'Boyle's theory of mobility vs. stability, in which the hip and pelvis are considered regions that tend toward stability. Now let's review simple screening procedures and movement pattern assessments for the lumbopelvic hip complex (LPHC) that can be performed in any treatment room.

The Modified Thomas Test

In 1998, Harvey used this test on 117 elite athletes and found excellent interrater reliability to differentially assess iliopsoas, quadriceps or TFL/ITB tightness. Harvey describes beginning the test with the patient lying supine at the end of the table, with both knees flexed to the chest to ensure complete flattening of the lumbar lordosis, and placing the pelvis in posterior rotation. One knee remains held to the chest while the side to be examined is lowered to the floor, and its resting position is assessed to determine soft-tissue compliance of the region.

Magee and Liebenson, however, describe the modified Thomas test as starting with the patient lying supine with both legs off the end of the table. The patient draws the unaffected side to the chest while the examiner observes motion of the affected hip. While Magee mentions this to be more effective in assessing rectus femoris shortening, Liebenson presents a more detailed differential assessment between iliopsoas, rectus femoris, hip abductor and hip adductor function. (Table)

|

||||||||||||||

Be sure to palpate the muscles involved for tightness vs. muscular contractures / spasticity vs. capsular or joint dysfunction. Always compare to the opposite side and be aware that there can be multiple imbalances.

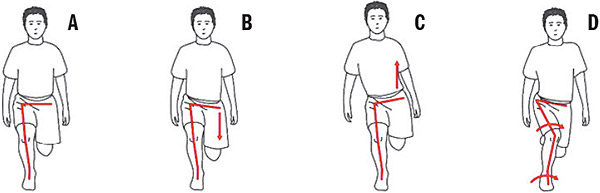

The Dynamic Trendelenburg Test

This test is essentially a single-leg ¼ squat and one of my favorites to assess dynamic stability of the entire lower extremity, not just the hip. Observe the kinematics of the entire lower extremity from the feet up. If during the test the non-weight-bearing hip drops, a positive Trendelenburg sign, this indicates the opposite gluteus medius is weak. Conversely, if the non-weight bearing hip elevates, it indicates overactivity of the ipsilateral quadratus lumborum in compensation for a weak contralateral gluteus medius. (Figure, b-c)

Beyond orthopedic and soft-tissue testing, thoughtful chiropractic rehab needs to evaluate the synergists, agonists, antagonists, prime movers, and stabilizers with movement, not just static assessment. This is where movement pattern assessments fall into your treatment and assessment paradigm: to evaluate if groups of muscles are working together in a coordinated manner to create functional movement.

When assessing movement patterns, the doctor needs to observe the sequencing of all the muscle involved as well as the overall strength. The goals is to analyze both the quality and control of the movement patterns because abnormal patterns will impact the kinetic chain both locally and regionally. Since this series has been focused on the lumbopelvic-hip complex, relevant movement pattern assessments include Janda's hip extension, hip abduction and trunk flexion.

Hip Extension Movement Pattern

This begins with the patient prone, preferably with the feet relaxed and off the table, and arms resting at the sides of the body. Instruct the patient to lift one leg at a time off the table and observe the movement and the muscle firing sequence. The motor sequencing for hip extension must involve a good contraction of the gluteus maximus.

Janda believes the hamstrings need to fire first, whereas the Sister Kenny protocols look for the gluteus maximus to fire before the hamstrings. Regardless, the bottom line is that poor gluteus maximus activation will lead to a dysfunctional movement pattern such as an anterior pelvic tilt or lumbar hyperlordosis.

The expected movement is for the leg to lift off the table from the hip with pure hip motion for the first 10 degrees, keeping the leg straight. Abnormal motion would be an increased lordosis, anterior pelvic tilt or flexion of the elevated knee (hamstring tightness). After the hamstrings and gluteus maximus, the firing pattern would be the contralateral lumbar erectors followed by the ipsilateral lumbar erectors. There should be no activation of the shoulder girdle muscles. Be thoughtful, assess the motion for efficiency and ensure all muscles are engaging completely.

Clinical Application: The latissimus dorsi is the only muscle to attach to the shoulder from the low back. Therefore, watch for latissimus activation during hip extension (an abnormal finding) in patients who have shoulder pain in conjunction with low back issues.

The Hip Abduction Movement Pattern

This begins with the patient lying on their side with the lower leg bent, the upper leg straight in line with the spine, and the hips and shoulders stacked. This test provides information on the lateral stability of the LPHC and involves of the prime movers of hip abduction: gluteus medius, gluteus minimus and TFL, as well as engagement of the quadratus lumborum and abdominal muscles that act as stabilizers for the pelvis during locomotion.

The hip abduction movement assessment is an observation of motion and activation of the above noted muscles in a synergistic fashion. The expected motion is abduction of the hip to approximately 20 degrees alone, without any hip flexion or rotation of the leg and with a stable trunk and pelvis.

Clinical Application: The patient has a hip hike with the dynamic Trendelenburg and demonstrates QL activation before 20 degrees of abduction in the movement pattern test. This combination indicates the QL has become a prime mover in hip abduction and is no longer a stabilizer, which in turn impacts LPHC arthokinematics.

The Trunk Curl-Up Movement Pattern

This is another assessment done to analyze the quality and quantity of motion. The patient is supine with their knees bent, feet flat on the table and arms on their thighs. Instruct the patient curl up until their scapulae clear the table. The expected motion is for the abdominals muscles to engage, the thoracic spine to round, the lumbar spine to flatten, the pelvis to tilt posteriorly and the feet to remain on the table. It is an option for the doctor to place their hands under the feet while performing the test.

Clinical Application: Anterior tilt of the pelvis and loss of pressure of the patient's heel in the examiner's hands indicates the hip flexors have become prime movers.

Getting the Most Out of Movement

There are a few caveats with performing any movement pattern test to ensure better outcomes:

- Do not touch the patient, as this can cause facilitation.

- Only give minimal verbal instructions.

- Perform the test three times, slowly.

- Disrobe as much of the body as possible to observe the patterns adequately.

Incorporation of active care in any chiropractic office can be achieved right in your current treatment rooms and with minimal cost. Your postural and chiropractic examination, enhanced by orthopedic, neurologic, functional and movement pattern assessments, will create a baseline for you to incorporate active care. After four weeks, re-evaluate the patient and address any imbalances appropriately. This is relevant rehab: thoughtful and effective.

Author's Note: Readers interested in obtaining the Movement Assessment Exam Form I use in our office can simply request it via email at .

Resources

- Liebenson C, Rehabilitation of the Spine, 2nd Edition. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 2007.

- Malagna G, Mautner K. Musculoskeletal Physical Examination, 2nd Edition. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier, 2016.

- Page P, Frank C, Lardner R. Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalance: The Janda Approach. Champaign IL: Human Kinetics, 2010.

Click here for more information about Donald DeFabio, DC, DACBSP, DABCO.