What is the biggest reason exercise programs fail? Patients don't enjoy them and fail to stick with them. Motivating patients to adhere and comply with exercise programs is one of the biggest challenges a chiropractor faces.

A new tool chiropractors can use to make exercise fun is the large inflatable exercise ball. This has been around for decades and has been used to treat children with cerebral palsy or vestibular problems. Now the ball has exploded on the back pain scene as a result of the pioneering efforts of Dennis Morgan and Eileen Vollowitz.1,2 They have utilized the concepts of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF), neurodevelopmental training, exercise physiology, and behavioral psychology to create a powerful system of training exercise.

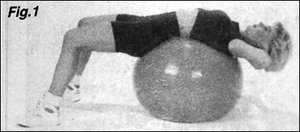

When patients see the ball it looks like fun -- after all, kids play with it. Once on the ball in the back stretch position patient's report that they can feel the lower back and shoulder blade strain of a full day's worth of sitting just disappear (see figure 1). This stretch is your patient's invitation to a new world of fun and effective stretching and strengthening exercises. Motivation is no longer a problem -- patients actually want to know where they can get a ball and what else they can do with it.

With the ball you can prescribe exercises for the abdominal, back, hamstring, quadriceps, and buttock muscles which train strength, endurance and coordination. The best part about the ball exercises is the abdominal and gluteal isolation that occurs from balancing on the ball during any exercise. This is the secret ingredient that makes ball exercises so important for stabilizing the back and improving posture. A 1994 paper showed that these exercises as part of "stabilization" and McKenzie program were the most effective treatment for failed lumbar laminectomy patients.3 Another paper in Spine used these exercises and successfully treated a large group of patients with back and leg pain who were referred for surgery.4 The best part about the ball exercises is that they help patients to hold their adjustments and feel better each and every day.

Most patients first learn about spinal stabilization on the floor. They learn to perform posterior and anterior pelvic tilts and develop awareness of motion at the lumbopelvic junction. Then they start to develop control of this movement as they incorporate proper pelvic positioning into simple bridging and curl-up routines. Progressions usually advance a patient rapidly to the point where they are able to feel a "burn" in their legs, abdominals, or gluteals yet without feeling any strain in their lower backs. This is the key to the stabilization program -- feeling postexercise soreness without increasing lower back or referred pain. Explaining to your patient that this is not about "no pain no gain" will relieve them of fear or anxiety which can immobilize them.

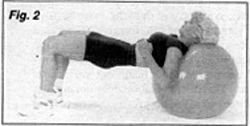

Once patients begin to understand the lumbopelvic movements progressions to upright and ball exercises are well tolerated. Bridging on the ball is an excellent way to train the gluteals without straining the lower back (see figure 2). In this exercise the patient learns to perform hip extension without increasing the lumbar lordosis. This is a basic skill which many people need to learn to prevent lumbar hyperextension during many activities of daily living such as hip extension during gait. By teaching the patient to perform a posterior pelvic tilt which they slowly bridge their pelvis up they will learn to articulate at the hip joint rather than in the lumbar spine. Many patients with instability do not control lumbar motion well and this training will re-educate their ability to stabilize their spine through coordinated movements.

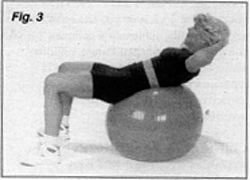

Another excellent exercise which patients enjoy is the curl-up (see figure 3). This abdominal exercise on the ball increases automatic reflex control of trunk and spinal posture as a result of having to balance. Patients reach a "burn" quicker on this abdominal exercise than any other and train the obliques simultaneously due to the labile nature of the ball.

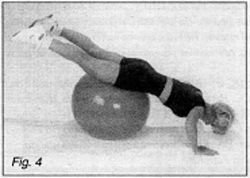

The back can also be trained in a variety of ways on the ball. One of the most effective is the "teeter totter" (see figure 4). Here, the patient learns to perform a posterior pelvic tilt and hold the spine straight while performing a push-up. As the torso goes down the feet rise up. The spine shouldn't lordose or kyhphose, but be held in a "neutral range" by abdominal and gluteal co-contraction.

Hundreds of ball exercises have been developed by Dennis Morgan and train the patient.5 Floor, ball, pulley, and gym equipment routines are all possible. Sometimes, such as in squatting, an anterior tilt is more biomechanically stable. Other times, such as in trunk curls, a posterior pelvic tilt is more desirable. Each patient has his or her own biases which also are figured into the equation for determining the amount of posterior or anterior pelvic tilt that is desirable.

Making exercises fun is the best way to motivate patients to do them. If we are to succeed in the challenging arena of pain management then addressing muscular deconditioning and spinal instability are surely important complementary procedures to spinal adjusting. Ball exercises also promote self-reliance and reduce patient dependency on passive interventions, and thus are ideal treatments for any patient, even those with chronic syndromes.

References

- Vollowitz E. Furniture prescription for the conservative management of low-back pain. Top Acute Care Trauma Rehabil 1988;2(4):18-37.

- Morgan D. Concepts in functional training and postural stabilization for the low-back-injured. Top Acute Care Trauma Rehabil 1988;2:8-17.

- Timm KE. A randomized-control study of active and passive treatments for chronic low back pain following L5 laminectomy. JOSPT 1994;20:276-286.

- Saal JA, Saal JS. Nonoperative treatment of herniated lumbar intervertebral disc with radiculopathy. Spine 1989;14:431-437.

- Hyman J, Liebenson C. Spinal stabilization exercise program. In Liebenson C (ed) Spinal Rehabilitation: A Manual of Active Care Procedures. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore 1995.

Craig Liebenson, DC

Los Angeles, California

Click here for previous articles by Craig Liebenson, DC.